Creating the Framework for Program Design

Level 3: Pro

Welcome Players! Creating an effective training program for a physical goal requires thorough planning and preparation. You can achieve great feats when prepared properly! And similarly can suffer costly defeats at the hands of a unforeseen error. Building a framework to create your program stacks short-term improvements on a clear path to success - breaking a program down into phases, macrocycles, and interventions helps create a clear line of thinking for an effective progression.

Contents:

Setting the Foundation

Work Big → Small

Break Down Phases

Fill in with Sand

Repeat the Process

The Warm-Up

Building upon the concepts laid out in Basics of Program Design and Program Design for Sport, this is a collaboration with one of our readers to construct a framework for a program made specifically for them. We’ll call this reader “John” for privacy, and will include their comments with permission.

You can re-create this process utilizing your own goals and purposes. This will help you create a well-thought out and structured program to set you up for success in your physical pursuits.

Setting the Foundation

The first thing needed when starting to build a program is clearly defined goals.

I asked John to answer the questions laid out in the Needs Analysis section of Program Design for Sport. These were his responses:

What are your goals?

“I want to be able to move more efficiently. I know that an hour of activity a day isn't nearly enough - so whenever I do get that time in, I'd love to be able to make the most of it and make sure I'm training optimally.

More specifically, when it comes to playing basketball - I'd love to get to a point where I'm moving pain free and not feel like a broken down car at the end of a hoop session (lots of soreness, primarily lower back and knees).

I'm approaching 30 and ultimately I'd love to be able to stay active playing sports, working out, etc. for the next 30 years”

What performance attributes are required?

“Strength (the kind you talk about in your articles), quickness, explosiveness, fast twitch reactiveness, ability to quickly and safely change directions, landing mechanics, proper loading, etc. (over time I feel like whatever shock absorbers I have in my legs have completely left the scene)”

What physical, mental, or environmental limitations are currently faced?

“Physical - aging process is likely a factor, though I feel that with proper programming there's a lot of room for optimization here

Mental - only mental blocker I'd say is "fail to plan, plan to fail" - when I don't dial in and commit to a plan at the beginning of the week it's easy to fall short of whatever I had set out to accomplish

Environmental - I'm easily sitting at a computer for 8-10 hours a day (Mon-Fri), I do make an effort to get up and move every now and then but the reality is I'm at my desk A LOT. That being said, I work remote so there is some flexibility to structure my days in my favor. Also, I'm really working on trying to sleep more. I'm not doing multiple coffees a day anymore and no caffeine after 4pm - I do go to sleep with the tv on still but it's easier for me to that way (at least I think so)”

What your strengths/weakness are in relation to goal?

“I feel like my current "programming" (or lack there of) is one of routine and convenience -lots of linear movements that don't really translate to real life movement patterns or the movements required to perform like the good old days on the basketball court

I typically lift weights 3-4 times a week (legs/push/pull) sprinkling in core strength in there as well - Saturday grinds are probably the most "functional" work I get in, and then basketball on Sundays”

Schedule notes:

“A good week for me tends to look like this:

Sunday - Basketball

Monday - Rest

Tuesday - Legs

Wednesday - Push or pull

Thursday - Push or pull

Friday - Rest

Saturday - [group circuit-style workout]”

We’ve identified the goals - movement efficiency, pain free basketball, longevity.

We have context for logistics - computer work 8-10 hours a day with freedom of schedule.

We know the relative resources - lifting weights 3-4x/week implies access to a gym with moderate equipment.

There is just one thing that we’re missing and that is some form of timeline. Without setting an amount of time to work within there is no relativity for deciding upon a conservative or aggressive approach.

So I asked John to attach his goals to a timeline he’s comfortable with:

Short term:

“By Jan 2023 I’d like to increase my activity throughout the work-day from 45 min cumulative to 90 min cumulative (combo of training + moderate activity).

By Jan 2023, I want to be able to play 60-90 minutes of unrestricted pickup ball without lower back / knee soreness during or after.

By Feb or March 2023, I’d like to be at X% body fat (whatever number you think will help me perform better).”

Long term:

“In 6 months time I’d like to be able to touch rim again.

Also, not sure how to measure my bodies efficiency to output energy, but in theory the over arching goal is to have all the muscles, joints, tendons, etc in my body working in sync to perform. If I was a car I want to run as smooth as possible.”

Excellent, we now have all the information necessary to build a framework for a program that he can use to work towards his goals in a progressive and efficient manner.

Start With the Big Things

The following video comes from a professor making a pointed lesson about how to prioritize your life. Spend your time wisely on the most important things and the rest will figure itself out. I’ll be referencing this video throughout the rest of this article so would recommend you watch it!

We can use this same approach for prioritizing the things in our program. Take care of the most important things first, and then fill in as necessary. The rest will figure itself out.

Identify the Important Things

From John’s needs analysis we can look to isolate what will make up the foundation of the program. The longer an adaptation takes, the more respective we have to be of including it in the process. If the goal involves multiple weeks of consistent effort, we have to prioritize that exposure over a goal that requires shorter term adaptations and then can try and elicit secondary adaptations that will cover those goals as well.

We’ll re-write his goals for clarity:

In 10 weeks wants to increase total activity from 45 min to 90 min each day through a combination of training and lifestyle activity

In 10 weeks wants to be able to play 60-90 minutes of basketball without subsequent soreness afterwards

In 14-18 weeks wants to be at an optimal body fat % for the above goals, deferring to me as which number that should be

In 24 weeks wants to be able to jump high enough to touch the rim of a basketball hoop

The thing that stands out to me the most is we’ve got two goals on the same timeline - 10 weeks to increase activity AND eliminate soreness post-basketball. This might prove problematic as I’ve talked about the dangers of trying to achieve two separate adaptations simultaneously.

We can adjust these goals to make our program more effective by introducing a slight variation. Especially because one goal is a lifestyle/habit change (amount of activity / day) and the other goal is a trainable (uninterrupted basketball), it makes sense to stagger these appropriately.

We’ll reduce the time it takes to introduce lifestyle changes to increase total activity. This is much easier accomplished and shouldn’t need to take 10 weeks.

Slightly increase the time target for getting to pain-free basketball. This allows us to be slightly more conservative in the approach which I tend to embrace as eliminating pain / dysfunctional soreness can backfire when done on an aggressive timeline. This also allows for a more structured periodization plan between the goals.

Now let’s put these goals in chronological order of which will be addressed in the program. I’ll fill in the adjusted timelines as well as our target body fat %:

Phase 1 - Increase total activity from 45 min to 90 min each day through a combination of training and lifestyle activity - 6 weeks

Phase 2 - Play 60 - 90 minutes of basketball without subsequent soreness afterwards - 12 weeks

Phase 3 - Reach 12 - 14% body fat - 16 weeks

Phase 4 - Have a vertical jump high enough to touch rim - 24 weeks

Break Out Each Phase

Now that we’ve got our golf balls in the jar (reference to video above), we can begin to break out each phase and add in the pebbles. To do this we repeat the same analysis as we did for the larger goals, except this time we’re zooming in on a more refined factor!

Phase 1 - ↑ activity time: 6 weeks

We know that John spends 8-10 hours a day at a desk working on the computer, but he works from home so has the ability to modify his schedule as needed. We also know that without a structure John often falls short of his activity goals, and that he occasionally get’s up from his desk but in no specific intervals. He has a time for exercise 5 days a week, taking a rest day on Monday’s and Friday’s.

In order to increase his activity, we’ll need to address two things:

Forming a plan on increasing day-time activity throughout the work day sans exercise

Using the 5-day exercise structure to build a baseline for our next phase which will be eliminating basketball-related pain

We’ll break down these points even further:

Increasing Day-Time Activity

For a 10-hour workday (assuming the upper limit), we ideally would want him to take movement breaks every hour. That likely is too aggressive of a change to make right off the bat, so we’ll progress into the change just like we would any other training modality.

We’ll start by introducing breaks every 2-hours throughout the work-day. We’ll implement a strategy of setting a 2-hour timer on either his phone or a web-based app that gives him objective time to take the break. We’ll also allow a 20-minute buffer for taking that break - if the timer rings and he’s in the middle of a task or a call he can finish with no stress of not adhering to the plan.

We’ll split these breaks into two categories: walks & stretching

Our goal will be a 15 minute walk on breaks 1 & 3 (hours 2 & 6 of the work-day)

On breaks 2 & 4 (hours 4 & 8) we'll introduce 3-5 stretches that will not only combat posture from working at a desk but will also begin to address common dysfunctions that could be contributing to knee and lower back pain from basketball. These stretches should take no more than 15 minutes as well.

With this change implemented John will be up to 60 minutes a day (30 of stretching and 30 of walking) of simple day-time activity. We haven’t even addressed his actual exercise routine and are already half-way towards his first goal.

The progression from the above implementations will start the first three weeks, while weeks 3-6 we’ll increase the time by 5 minutes for both the walks and stretch breaks, leading us to achieving 80 minutes of activity that combat the sedentary nature of his work.

We can further progress this by introducing more breaks or different types of breaks. Instead of walking it’s yoga. Instead of stretching it’s ground-based movement drills. Once you have the framework how you fulfill it is up to you.

Exercise Routine

We don’t need to change the split he’s using for exercise as it’s set-up well enough already, but we will provide guidelines on what those workout routines should look like for the first 6 weeks of phase 1. Remember our identified goal of this exercise routine is now to build a foundation that will allow us to transition to eliminating dysfunction in the next phase which will be weeks 6-12.

With this in mind we know that his training attributes should focus mostly on muscular and cardiovascular endurance (the ability to tolerate higher volume), proper exercise technique, and a focus on the training movements that combat most common forms of low-back and knee pain in basketball players.

Without getting into the specific exercises and set/rep schemes (this is a framework, not the actual program), based on common injuries and deficiencies seen in the sport for the problems he’s dealing with John should address the following in his program:

An effective hamstring-to-quad strength ratio (3:2)

Adequate muscular endurance of his posterior chain

Ankle & knee (flexion) mobility

Full activation of the hip extensors

Core control and stability

Static single leg balance and stability

Using the above as a guideline he can fill-in the appropriate exercises and volumes, which would be akin to the sand in the jar from the video example.

The more clearly-defined we make the more important items, the more freedom we’ll have when getting down to the details. In a program that follows the above structure, there is tons of room for different exercises and volume/intensity schemes that even when not optimized will still lead to the achievement of his goal within the desired time.

Fill in the important things first if you want to have this freedom!

Repeat The Process

We’ve clearly identified John’s goals (the jar) through a needs analysis. We then broke down his goals into phases (golf balls) with clearly delineated timelines for accomplishing each. We broke down Phase 1 into two primary interventions (pebbles), and then offered a variety of things to include in the specifics of those interventions (sand). When the sand is filled in for the exercise routine, he will have a comprehensive macrocycle for Phase 1 of his program!

This same process is then completed for Phases 2, 3, & 4, progressively breaking down the larger goals and phases into more digestible steps and interventions until finally being completed with the specific training modalities and volumes.

When constructing a program you should not look to achieve the “perfect program”, you should look to create a program that allows you to achieve your goals in a set amount of time accounting for unplanned obstacles and life changes. A strict and rigid program that doesn’t have any freedom of change will fail when stress-tested by interruptions or unforeseen circumstances.

Focus on breaking down goals into phases, macrocycles, and subsequent interventions so you can insulate the program from any one piece becoming destructive to the rest of the program should it fail. This creates a layered framework.

If John is suddenly overloaded with work where he cannot maintain the structure of breaks AND exercise time, he can self-select which is of higher priority to maintain while temporarily eliminating the other. Let’s say he chooses to pause his structured exercise routine and maintain his 2-hour breaks, he then has enough time to handle the increased workload and will not be losing progression towards his goals if he maintains intermittent activity. His exercise routine may be cut down from 5x/week to 2-3x/week, but that’s OK. Fulfilling his work responsibilities is clearly the highest priority, and the program has room to make these adjustments on the fly. When the work obligations return to normal, he can seamlessly re-integrate back into the full exercise routine without stress or worry.

This is the beauty of a well-designed program.

Conclusion

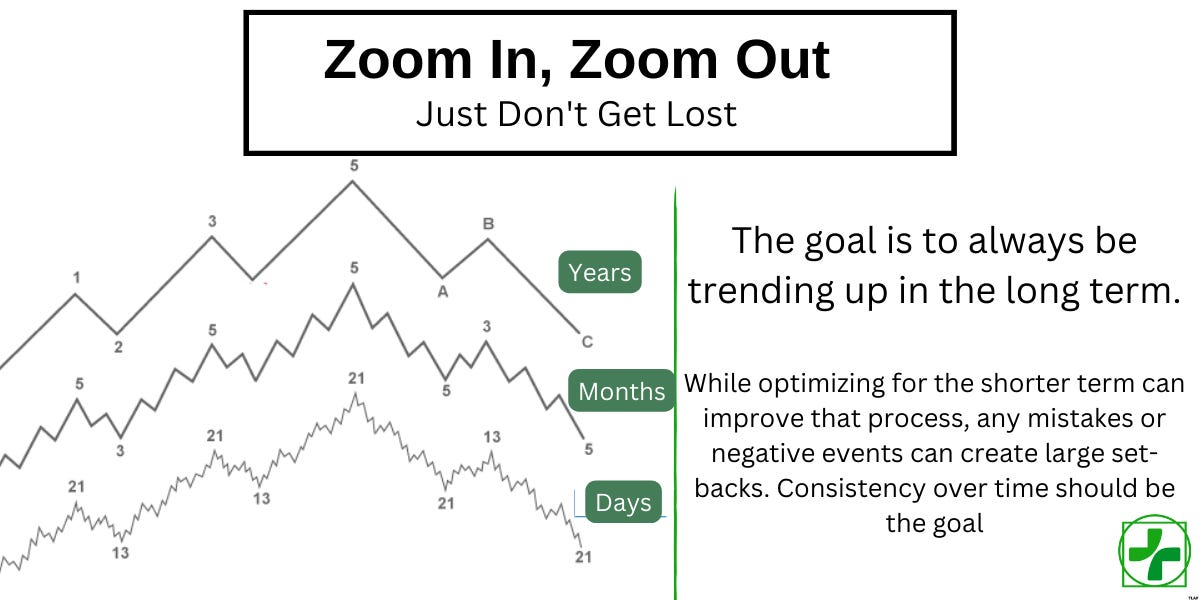

The most critical part to building a great program is thoroughly thinking through these steps and accounting for making changes on a long-term horizon. Always be trending up. If you have that set as your foundation, and properly program for it, you’ll have all the freedom to work on optimizations in the short-term to improve the process.

But if you don’t have good long-term planning, and you get stuck in a cycle of only working on short-term optimizations, then sooner or later the lack of long-term preparation will catch-up and expose weaknesses.

While I won’t be outlining the same process for the rest of the phases, I will do my best to answer any questions as it relates to John’s sample program or the process discussed throughout. Leave a comment with your question below!

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice. The content is purely educational in nature and should be filtered through ones own lens of common sense and applicability.