Program Design for Sport

Level 3: Pro

Welcome Players! An effective program creates a structured plan of specific stress designed to elicit a specific adaptation at a specific time. This is done in a progressive fashion over a period of days, weeks, months and years to optimize performance. Starting with a needs analysis, a periodization plan, and the right combination of training modalities you can significantly improve the efficiency of which you accomplish your physical goal.

Contents:

Programming Considerations

Periodization

Training Methodologies

Conclusion

Programming Considerations

To program means to create a plan and structure to accomplish your goal over a finite amount of time.

No different than business plans or marketing strategies, a training program is made up of actionable steps over different time periods to collectively accomplish a desired goal. What this article covers are different factors to consider when building a program for you or someone else.

Needs analysis

You’ve got to know where you’re going before you figure out how to get there.

Identify:

What your goals are - be specific

What performance attributes are required

What physical, mental, or environmental limitations you currently face

What your strengths/weakness are in relation to goal

This will make-up the framework of your program. The more in-depth you’re able to identify these needs the higher specificity and effectiveness your program will be in addressing them.

Logistics

Plan your program around your life, not your life around your program.

If you don’t account for your lifestyle and responsibilities during programming when push comes to shove your program will fold. The ‘ideal’ program is one in which you can provide high-effort work consistently. The art of programming is utilizing this to compound progress over time.

You could be as minute to optimize circadian rhythms and hormonal fluctuations to best structure a workout at the specific time of when these processes peak, but when life gets in the way a training program that lacks flexibility or adaptability will cause the you to miss sessions. Or even worse, undergo a training session without proper recovery / preparation causing an injury that can significantly delay you.

When you are constructing your program make sure to account for logistics, both on a small and large scale.

This means pairing exercises or movements with similar equipment or located in the same training area, not having to traverse across the training facility in between sets. While you might think this means being lazy, it’s absolutely not. As mentioned in programming basics, the time of rest intervals ensures you’re eliciting a specific adaptation, which means getting more rest because logistically changing exercises is actually causing a negative impact on the training session.

On a larger frame, scheduling training sessions around higher-priority life events is paramount. You should not plan to peak in a cycle at a time when there is a major event. If you have a training session scheduled for Monday morning where you are expected to hit 90% of your 1 RM for multiple sets and you were traveling or worse, partying, over the weekend you’ve reduced your potential for an effective session before even showing up. Logistical considerations within your programming addresses these problems before they arise.

Resources

You can only work with what you’ve got.

While everyone would love to have access to the best equipment, that’s not a reality. Being prepared to develop your program with as little resources as possible allows you more freedom to adapt when better equipment becomes available.

If you prepare for having certain equipment available in your program and that equipment is no longer available, it can be difficult to scale down or to another variation.

When programming you should keep in mind potential equipment and resource limitations, as well as have multiple variations in the back of your mind or even pre-programmed should your desired equipment be unavailable.

Building Athletes, not Bodybuilders

Unless of course bodybuilding is your purpose, the goal should not be to train like a bodybuilder, or any other sport for that manner.

The goal is to train safely and efficiently to fulfill your athletic potential and achieve what you set out to accomplish. Train for your goal.

While utilizing training modalities or structures from other sports may be useful in a specific portion of your program, you want to be wary of falling into a trap of training exclusively for another purpose hoping the improvements carry over to your goal. (ex: a basketball player exclusively training for vertical jump height - at some point on the curve that time would be better spent elsewhere to improve overall performance)

If your goal is to train for strength, bodybuilding (hypertrophy-based workouts) can certainly hold a phase within your program, but you’ve got to be able to move out of that phase into a more direct approach for your goals: Strength!

Similarly, if your goal is to increase your 40-yard dash time, weight-room exercises focusing on lower body strength and power will certainly help you get there, but it is imperative that you progress out of the weight room and onto the track. You’ve got to sprint!

Exercise Selection

Train movements, not muscles.

This is a key to amplifying athletic potential. Muscles create force, but movements create actions!

When you’re training for athleticism you want to be increasing the efficiency at which you complete a task. Sometimes improving force output is helpful, sometimes there are more efficient ways to improve performance such as improving the quality of the movement or training for a non-force producing strategy such as footwork or body organization (how your body moves in space in relation to itself).

Periodization

Truly mastering programming means utilizing individual training sessions to elicit a specific adaptation that progresses into not only improvement in sport, but maximizes performance potential at the right time.

Periodization is the phasic method of manipulating training variables in order to increase the potential for achieving specific performance goals over an extended period of time.

For a prime example we look at training or competing in an Olympic Sport. The Olympics happen once every four years, so an athlete who’s competing needs to structure their programming to peak at the end of that four year gap to maximize performance and give themselves the best chance at winning gold.

Over that four year cycle, there are local, national, and international competitions that the athlete must perform at to not only qualify, but to solidify their skills against the top competition.

So within the four year cycle of Olympic competition they need to maximize performance at intervals along the way, ensuring the entire time that their training is contributing to local peaks in performance (months) and global peaks (at time of event). This is truly a difficult task and what makes a properly periodized programs so valuable.

Supercompensation

As it relates to athletic performance, supercompensation refers to the theory that when you train to elicit a specific adaptation followed by structured rest periods, the resultant adaptation will exceed the previous levels of performance.

The goal of long-term training programs is to elicit supercompensation in a progressive fashion so that improvements are stacked on top of each other in a way that continues to elicit positive adaptations without incurring injury or overtraining. No easy task.

Utilizing theories of supercompensation and training cycles, athletes can achieve performance improvements over the long-term with consistent training. The goal is to achieve optimization in performance that looks something like this:

Overtraining

While proper programming looks to optimize performance potential, it’s also used to safely avoid overtraining. With the method of supercompensation you are pushing your body towards its limits in tolerating stress, and as such need to provide appropriate rest and recovery to allow the regeneration and adaptation process to take place.

Repeat training sessions too soon without adequate recovery and you will train too early on the supercompensation curve decreasing performance and adding cumulative stress. Over time this stress builds up and wreaks havoc on physiological performance.

This can lead to physical injury, mental injury (burnout), or other systems of the body breaking down such as the immune system (getting sick), lymphatic system (not processing inflammation), or nervous system (chronic fatigue).

The important part is to keep going. Consistency. Over. Time.

There will be ups and downs, so long as you continue along a well thought out plan and adjust along the way, you will get there.

Periodization Theory

There are four principles that fueled traditional periodization:

Principle of cyclical training design - idea that because the body adapts to stresses placed upon it; a variety of stresses designed to elicit different adaptations needed to be cycled in order to achieve maximum benefit between each variable over a longer period of time while continuing to improve at the sport

Unity of general and specialized preparation - an athlete needs to maintain levels of general conditioning while adapting to the performance specificity required of their sport

Wave-shape design of training workouts - the relationship between exposing an athlete to volume in relation to rest and the supercompensation cycle in order to prevent overtraining and decreases in performance. Often times this was realized in sequencing of high-, moderate-, and low-load volumes across different periods of time

Principle of continuity - when placing stress upon the body for adaptation, there is a need for structured breaks or dedicated rest periods that allow for not only recovery and adaptation but also for the athlete to maintain a personal life for the holistic benefits that brings

These principles created the framework for incorporating a series of training cycles on different time-frames that could be used to tailor training in a progressive fashion leading to peak performance at the time of competition.

Traditional Periodization

A traditional periodization model utilized phases of intensities/volumes while trying to simultaneously elicit multiple adaptations. By the end of the periodization the athlete would be left with a peak in performance right before competition period.

Once the competition period started, then the goal of performance improvement was abandoned in favor or sport-specific practice and doing their best to maintain gains in the off-season until the competition period was over and improvement could begin again.

Utilizing this set-up of training cycles the athlete would go through the following phases:

Preparatory

Competition

Transition

These three phases could be broken down into smaller/more refined components, but the foundation is a preparation phase which is be made up of high-volume, lower-intensity work; followed by the competition phase of low-volume, high-intensity work; completed by the transition phase which acted to shepherd the training off of the competition period back to the preparatory phase for the next cycle.

Traditional periodization only works well when there’s a defined competition period and you do not have to account for multiple peaks throughout the year. For individual sports such as swimming, tennis, golf, etc. where there is no defined competition period rather competitions spread throughout the year, traditional periodization lacks true optimization of performance.

Block Periodization Model

The more modern approach to periodization that accounts for multiple competition peaks throughout a year (or multiple years) was created by training a limited amount of specific adaptations in a timely manner in a ‘block’. This differs greatly from traditional periodization which attempted to train multiple adaptations simultaneously within the respective phase.

In block periodization you are seeking one main adaptation and maybe one or two accessory adaptations while undergoing more phases in shorter periods of times.

There are a few principles that block-periodization takes advantage of allowing for multiple peaks that the traditional models do not emphasize:

cumulative training effect - physiological and biochemical variables must be developed over long periods of time to elicit adaptations specific to the sport

residual training effect - the amount of time a specific physiological adaptation can be maintained once training for that specificity has stopped

Block periodization allows athletes to have multiple peaks because they are altering between cumulative training effects and sport-specific training abilities in shorter periods of time.

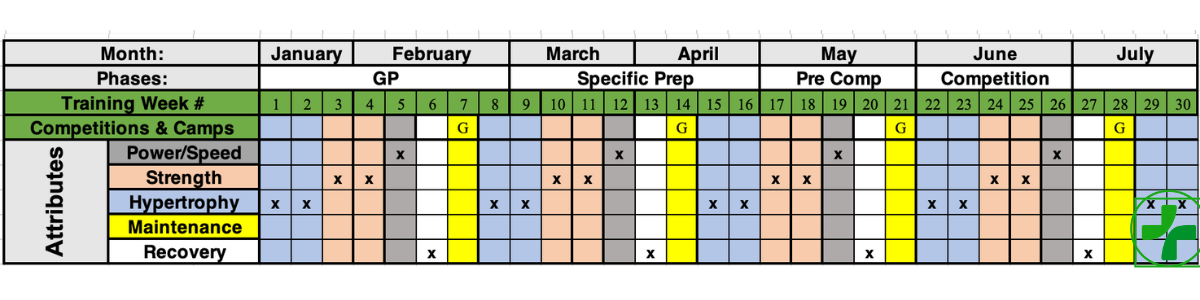

In the example above, we can be confident that the hypertrophic gains made in week 1 and 2 will hold residually throughout weeks 3, 4, and 5 as we transition to more strength and power-based work. It is a lot easier to maintain progress in one variable while improving another than it is to make progress on multiple variables at the same time.

As you go through four of these cycles throughout the first 6 months (in the example) you will have cumulative gains in each variable that optimizes performance during the competition periods (weeks 7, 14, 21, and 28) while also continuing progress over the long-term - week 1 compared to week 29.

This is the beauty of block programming and why it has grown to dominate sport performance training.

Training Session Methods

The following are a variety of methods that are commonly used to structure a training session, the smallest time-frame in our program. This is not an exhaustive list, nor is it meant to be a conclusive how-to guide on executing them. The purpose is to expose you to the possibilities with enough information that you can determine which is most appropriate for your purposes and to stimulate further knowledge-seeking to implement it.

Pyramid sets

Made popular via bodybuilding, pyramid sets are created by using a progressive increase in weight with a decrease in repetitions performed.

Purpose: Maximizes loading while limiting fatigue to optimize adaptations generally in an end-hypertrophy or strength phase.

Contrast training

Utilizing the post-activation potentiation (PAP) principle, contrast sets utilize a heavy strength exercise followed by the same movement in a power/plyometric fashion. Increases activation of fast-twitch muscle fibers with heavy load and then applies those same tissues/fibers into a high-velocity movement.

Purpose: Increases activation of fast-twitch muscle fibers with heavy load and then applies those same tissues/fibers into a high-velocity movement. Causes an increase in short-term power output via higher-recruitment of fibers for a specific muscle.

Example: Back-squat for 4 repetitions @ 90% of 1 RM followed by 5 vertical squat-jumps.

Complex training

The same principle as contrast training utilizing the PAP principle except with a slightly different application. Complex training involves a more sport-specific plyometric movement along with a variably longer rest interval.

Purpose: Used in phases closer to competition periods to train the integration of weight room strength into sport-specific power / velocity. Longer rest times focus on optimal performance of movement instead of increasing stress to the muscle (as in contrast sets).

Example: Back-squat for 4 repetitions @ 90% of 1 RM, 4 minute rest interval, followed by a max-effort sprint.

Combination exercise

Exercises that literally combine two different exercises into one performed repetition due to the positional advantage from one to the other.

Purpose: Combination exercises are used to increase the efficiency with which force moves along the kinetic chain, or to train movements in a multi-dimensional fashion that is more applicable to sport.

Example: Front squat to overhead press. When you complete a front squat, you’re in the start position for an overhead press, which you then complete next. The combination aspect comes from reducing or limiting the pause-time in between the two exercises. Coaches note: a lot of these times these combination exercises are given their own name, such as this movement being called a “thruster” by some. The terminology doesn’t matter as long as you understand the concept.

Compound exercise

Similar to a combination exercise where two different exercises are performed with each other, except in a compound exercise there is a clearly delineated stop-start when transitioning to the second part.

Purpose: Compound exercises are used to increase the metabolic demands of a workout and can be used to address specific energy systems within multiple movements.

Example: Front squat to overhead press. After completing the front squat, there is a clear pause/re-set to stabilize before then completing the overhead press.

Supersets

A pair of two exercises that have a distinct transition between them but performed in rapid succession.

Purpose: Mainly to increase volume within time-constraints, supersets are ideal in a pair of exercises that do not use the same muscle groups to avoid fatiguing energy systems and affecting the second exercise.

Example: Supersets of pull-ups & squats; deadlifts & bench press.

Circuits / Stations

Circuit-style training or via stations is setting up an exercise routine in a preferred order with pre-programmed work:rest intervals and intensities. The key to a circuit- or station-style workout is the exercise selection and work:rest ratios depending on the goal and desired adaptation.

Purpose: To focus on metabolic efficiency and energy system development while spreading out muscular effort throughout the entire body.

Example: A four station set-up consisting of:

20 yards of rope pulls

25 yards of sled drives

35 seconds of sledge hammer swings against a tire

40 seconds of battle ropes lateral swings

4-minute recovery

Repeat for prescribed rounds

There are also other forms of work such as strip sets, drop sets, overload sets, concentric/eccentric only work, etc. To detail every form of training methodologies in programming would be akin to writing a textbook, of which I will provide further resources at the end of this article.

Programming - Science + Art

While there is a plethora of information, even more so than provided here, knowing the science of training modalities and exposures in order to elicit specific adaptations just provides the framework. How you put that science together, in what package, order, volume, etc. is the difference between master programmers and beginners.

A good friend of mine is a chef, and I once asked her if she was ever worried about another chef/restaurant stealing her recipes. I’ll never forget what she said, “I’ll give ‘em the damn recipe, they still won’t be able to make it like me!”

The same is true for putting together an effective program. You can give two people the same exercises and come out with two totally different programs.

Don’t get locked into one method or approach. Continuously test out new concepts, try different pairings or sequences, see how your body responds to different stimuli. What works best for you and your lifestyle may not work best for someone else.

Coaches note: I am available for programatic consultations. Contact below for more information.

Advanced Reading:

Anything from Tudor Bompa

Anything by Yuri Verkoshanksy

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice. The content is purely educational in nature and should be filtered through ones own lens of common sense and applicability.