Low Back Injuries in Golf

Level 4: All-Star

Welcome Players! Low back pain is the #1 injury in the sport of Golf, yet golfers are no more likely to suffer from a spine injury than any other sport. Injuries can occur when mobility is limited creating an inefficient movement pattern, and that pattern is repeated beyond a tolerable volume. If you do suffer disc injury, the outlook is positive given that you follow a comprehensive rehabilitation program and will be able to return to the sport you love without any significant limitations.

This article details how back injuries occur, what factors are considered in treatment and management, and the requirements to making a full recovery. Let’s go!

Contents:

The Warm-Up

Injury Prevalence

The 4 Types of Injuries Causing Back Pain

Intervertebral Disc Injuries in Golfers

Surgical vs. Non-Surgical Intervention

Recovery Outlook

Final Thoughts

The Warm-Up

It’s important to set the parameters and context for this discussion surrounding injuries, injury management, and rehabilitation.

First, pain is multifactorial, injuries are complex, and no singular biomechanical diagnosis makes up for the entirety of an athletes symptoms.

The prevalent model for pain is some variation of the biopsychosocial model, which as the name implies is a combination of biological, psychological, and sociological factors that influence the presence and persistence of pain.

A complete accounting of all the factors that influence back pain in the sport of golf belongs in scientific literature, not in the Train Like a Pro Library. This article is intended to provide insight into what that literature says, not replace it entirely. For further information please defer to the research in the linked & cited resources.

Second, this article is not meant to diagnose or speculate on another person’s medical injury. Please do not take it as such.

And third, in addition to the scientific knowledge available to me, I write this with a unique perspective on the topic of disc herniations and return to play in golfers: as I’ve lived through the experience myself.

In 2015 I herniated a disc at L4/L5 and had a microdiscectomy procedure (with a laminectomy) to correct it. The surgery was successful, and I spent the following years rehabilitating myself with nothing but my own knowledge of movement and exercise.

It was not easy. I made many mistakes. It took much longer than it should have. All these things are true.

But in the process I learned far more about back pain and the recovery process than any textbook or formal education could teach. I learned about how minute movements can trigger severe symptoms. I learned about how having your movement taken away can create bouts of depression. I learned how restoring proper intra-abdominal pressure via breathwork and utilizing decompressive techniques to coordinate muscles of the abdomen are absolutely vital to restoring function to the core and being able to return to sport.

It wasn’t until last year did I make a commitment to pursue golf in lieu of other athletic sports, with the full knowledge that my prior injury and subsequent recovery would be considered by most as a limiting factor. But I knew better.

As we’re going to explore, golf is no inherently more damaging for the spine than any other activity. Not only will I provide the supporting literature to back this up, but my personal experience validates this ten times over.

Injury Prevalence

Many assume, or are tempted to think, that because golf is a high-velocity rotational sport that every golfer is destined to have back pain and that it’s due to the demands of the sport.

But what does the scientific literature and statistics say?

The total injury incidence in golf somewhere between 15-40% annually (31-90% in Professionals)

0.28-0.60 injuries per 1000 hours in amateurs (more in Professionals, because professionals play more)

Most frequent cause of injury is volume of repetitive practice

Lead side arm & leg is more often injured than trail side, and spine/lower back make up greatest incidence of injury in amateur golfers (18-36%) followed by elbow (8-33%), wrist/hand (10-32%) and shoulder (4-18%)

Overall, incidence of injury is moderate and rate of injury per hour played is low1

Compared to other sports, Golf had one of the lowest incidences of LBP along with Shooters and Triathletes.

The systematic review from which the above graphic was taken had the following conclusion:

“This finding is in line with the study by Vad et al. [29] which reported that only 33% of golfers experience LBP during the life time, which is lower than all other athletic groups and the general population [57]. Previous basic studies have shown that a golf swing generates significant rotational forces in the lumbar spine, which has led to many expert opinions regarding a high prevalence of LBP in golfers [58–60]. Low rates of point and life time prevalence of LBP among golfers from this review seems to contradict that thought process. It is not clear if golf is protective of LBP or if this result is due to a selection bias.” 2

Based on these findings, it is clear that the sport of golf has no greater pre-disposition to back injuries than any other sport, and that pain or injury stems from improper technique of repetitive motions along with failing to appropriately scale volume, load, and/or intensity of training.

With that out of the way, let’s get into what back injuries we do see in the golf population and why they occur.

Common Types of Injuries Causing Low Back Pain

There are four structural injuries that golf-related back pain can be attributed to:

Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

Spondylolisthesis

Facet Joint pathologies

Intervertebral Disc pathologies

While the scope of this article will be focused on disc pathologies and their management, it’s important to understand the relationship that other structural injuries can have.

Sacroiliac Joint (SIJ) Dysfunction

SIJ is a catch-all term for pain and dysfunction at the sacroiliac joint.

The SI joint is responsible for transmitting force between the upper and lower body. When you sprint, jump, throw, or perform pretty much any compound movement, the force generated in the lower body travels through the SIJ in order to get into the torso.

No different in the golf swing - the ability for the SIJ to transmit forces from the lower body, through the pelvis, into the torso is vital to an efficient swing.

SIJ dysfunction occurs when there is either too much movement between the pelvis and sacrum causing a sprain of one of the many thick SIJ ligaments, or when the tension in the muscles of the hip are no longer working together to stabilize movement of the pelvis and that force transmission is disrupted.

If an athlete is not moving efficiently and cannot transfer force through the SIJ without pain or uncomfortableness, their lumbo-pelvic complex stiffens and limits movement capabilities at that segment. This can create compensatory movement at the lumbar spine which can lead to other problems.

In order to create the same global ranges of motion, the body works to create motion above the pelvis, AKA at the lumbar spine. When the lumbar spine begins to rotate too much, well, that can lead to a disc pathology.

In Simple Terms: Sometimes the ligaments of the SI joint can become stretched creating a sprain. The body will then protect the site of injury by limiting movement at that joint and ‘stealing’ motion from another joint in order to accomplish the same task or movement. When the pelvis or thoracic spine does not move well, the compensation often comes from increased motion at the lumbar spine leading to an increase risk of injury.

Spondyloslisthesis

[Spaan-duh-low-luhs-thee-suhs] or Spondy, as the term is shortened too, is when there is excessive motion between two spinal vertebrae’s. It can be thought of as spinal instability at a specific spinal segment.

Often times the spondy itself is not the cause of pain, but it’s the damage or degradation caused by the excessive motion that creates injury.

If the lower vertebrae is posteriorly shifted and the spine is then brought into extension, this can cause the posterior process to impact the one above it. This can lead to a fracture of the bone.

The instability over time can also cause wear and degradation of the discs, and some disc injuries are not caused by traditional mechanisms any more than they are by a undiagnosed spinal instability.

While traditionally spondy’s are relatively rare in a diagnostic setting, in my experience they are much more common than most clinicians realize.

Spinal instability caused by aggressive swing speed practice in combination with lack of proper training and abdominal pressure is a recipe for non-acute low back pain.

Restoring proper activation to the stabilizing muscles of the spine (multifidus, erector spinae) and re-organizing proper intra-abdominal pressure through the core is crucial to re-stabilizing the dynamic relationship of the vertebrae and avoiding further progression of the spondy or other injury.

Facet Joint Pathologies

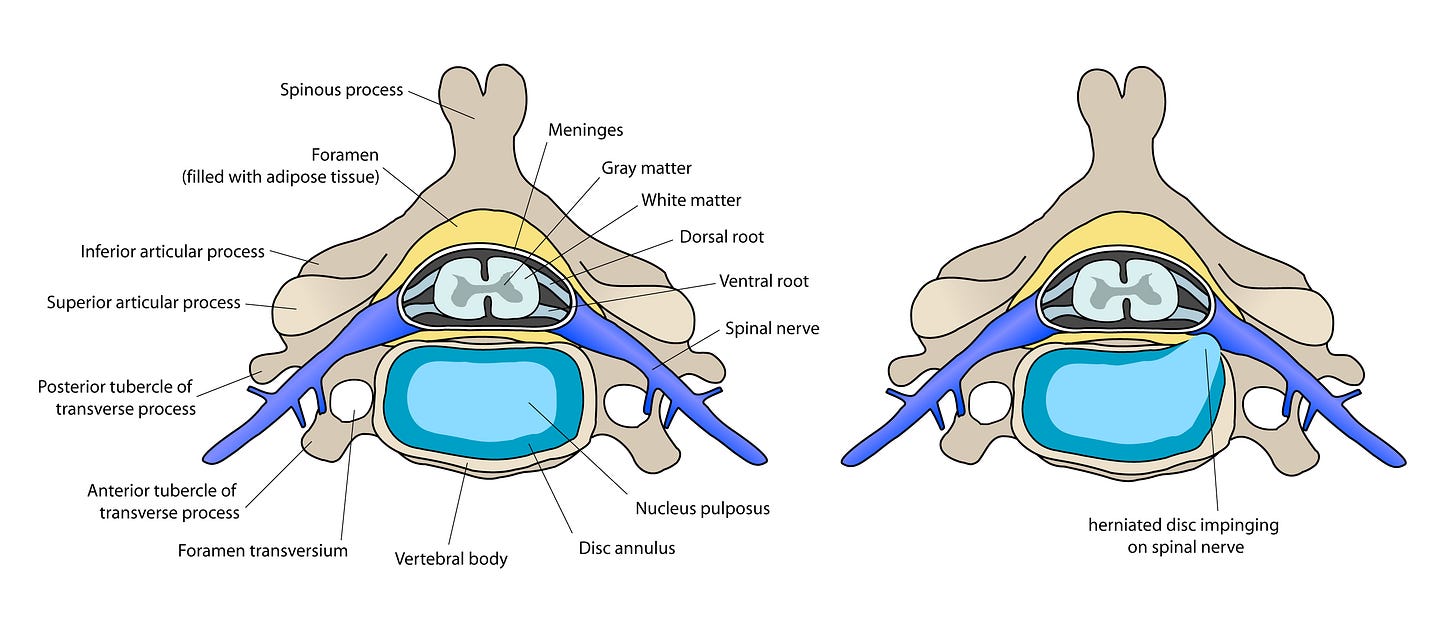

The facet joints are the interaction between the lateral processes of the vertebrae that allow for controlled flexion and extension with articulation of the intervertebral disc.

When the spine bears too much weight, or is compressed, the facets can wear on each other causing inflammation and pain.

They can also become problematic from excessive uncontrolled range of motion.

While facet joint pathologies are not an common injury, they do account for a percentage of back-pain and are common with other spinal injuries such as disc pathologies.

Along with compounded issues we see from injuries such as spondylolisthesis and facet joint pathologies is that they both increase the risk of damage to the intervertebral discs.

It is not so simple as to separate each structure and it’s respective damage as the singular injury that’s responsible for pain. The reality is that all of these structures have interaction that makes movement possible, and damage or dysfunction at one will inevitably lead to an increase risk of damage or dysfunction at another.

Intervertebral Disc Pathology

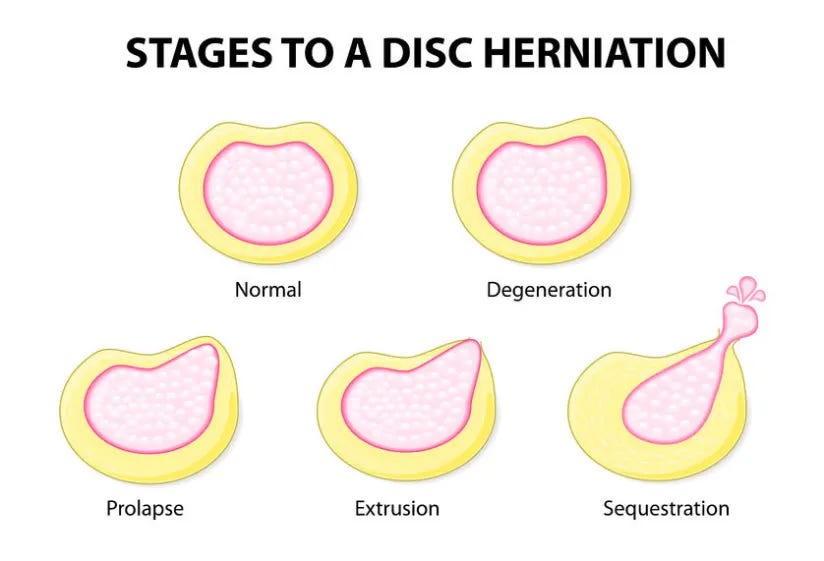

A disc herniation occurs when part of the intervertebral disc breaks through the sac holding it together and begins impinging on either the spinal cord or one of the spinal nerves leaving the spinal cord.

An easy example is to think of a Boston Cream donut (yum).

The cream of the inner filling is the nucleus pulpous, a soft jelly-like substance that makes up much of the discs force-transmission capabilities.

The dough is the outer layer, the disc annulus, that holds the cream on the inside and prevents it from leaking.

When a disc herniation occurs, it’s like you took a bite out of the donut allowing room for the cream to escape. What a mess! If it’s on a plate you can clean up the cream with your finger and eat it like frosting - delicious.

But in your spine there’s many other structures that are extremely sensitive to pressure and impingements. When that nucleus pulposus material starts to impinge on parts of the spinal cord or spinal nerve roots we can get all sorts of radicular symptoms ranging from sciatica to excruciating lower back pain.

Extensive research has proven many times over that repetitive spinal flexion combined with spinal rotation, especially under load, is a primary mechanism for injury to the intervertebral discs.

A powerful golf swing is one that occurs on high amounts of lumbar spinal flexion and lateral flexion whilst performing rapid rotation throughout the hips and thoracic vertebrae.

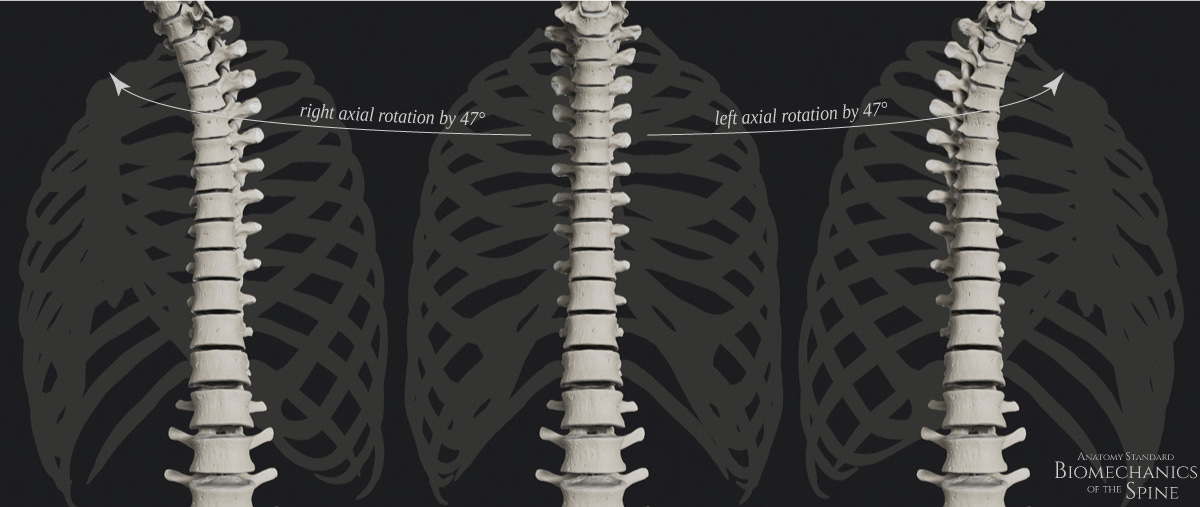

The lumbar spine averages ~5 degrees of rotation (~1 degree in each vertebral segment), and thus does not make for very good rotational capability.

The thoracic spine on the other hand can account for up to 47 degrees of rotation, along with having smaller vertebral bodies make for excellent rotational capabilities.

The problem arises when there are rotational deficiencies above or below the lumbar spine, such as in the hips and/or thoracic spine. If you are trying to rotate and don’t have the prerequisite mobility, your body will create motion in other areas to accomplish the task. When this happens the lumbar spine can rotate beyond it’s optimal ranges.

Over time these deficiencies repeated over enough repetitions can create compressive and shearing forces on the disc that increase the potential for injury. Which golfers get injured and which don’t is a complex equation based on their entire lifetime habits and movement proficiencies as well as their physical resilience.

Most often disc injuries do not occur as a result of one acute movement or injury.

There is a studied progression to injury occurring to the disc, which is that disc injuries occur after repeated movements that require spinal flexion + rotation, especially under load.

While it’s certainly possible for a disc injury to occur at a singular moment with pressure within the disc exceeding the physiological capacity, this is rarely the case.

Even in athletes who experience an acute injury, the progressive degeneration of the disc due to poor mechanical management and movement progression is more likely than not the underlying cause.

With this information it is tempting to say that the golf swing is a biomechanically damaging movement for the spine and that humans were not “meant” to do it - but I challenge that humans were not “meant” to do many things.

Looking at the statistics presented in the first section we also have objective data to say that this is just not the case. When the incidence of injury in golf is in the lower-half of back injuries across all sports, it is far more likely for us to assign injuries in golf to the same reason all spine injuries occur:

Improper training, improper technique, poor load management, poor volume management, and otherwise absence of preventative care.

In a mechanically efficient golf swing in which the player has adequately progressed his practice the swing mechanism poses no greater threat than any other sport specific movement.

So when we talk about why might a golfer sustain a disc injury it’s no different a conversation than saying why does anyone sustain a disc injury.

There was likely a perfect storm of a few events (in no particular order):

Repetitive exposures of a movement

Limited flexibility of the joints above & below the lumbar spine

Compensatory & excessive movement at the lumbar spine

Inadequate load management and progression of exercise

Lack of sufficient intrabdominal stability

Mix these together and you’ve got a recipe for a disc injury that can be set off by either one aggressive acute movement or simply a slow degradation until symptoms appear.

Injury Management

Ok, so someone presents with a disc injury. What now?

The first order of events in an injury with significant symptoms (numbness/tingling, sciatica, reduced strength in leg, etc) is to get an MRI to understand the level of impingement on the nerve root.

This step is important because if the impingement is severe it can cause significant long term damage. It’s more of a precaution than anything, but if you want to accurately assess your options and likelihood of full recovery having the image allows for better decision making.

The outlook for disc injuries is much higher than people think. It is most certainly not a sentence for surgery just because you have objective impingement and symptoms.

We can break down treatment options into two buckets: conservative management or surgical intervention.

Conservative Management

With conservative management you are opting for an extended rehabilitative period where the goal is to use movement, exercise, and other holistic interventions to reduce inflammation and attempt to create space & stability within the vertebrae so that the disc can re-absorb back into position.

This meta-analysis found that there is a 2 out of 3 chance that patients recover via resorption, a smooth 66.66%. Much more likely than most people realize!

Of course this can take anywhere from 3-12 months, but being early in implementing a treatment protocol as well as utilizing a comprehensive holistic approach can improve this number as close to 85-90%.3

The treatment is relatively straightforward, although not as easy as it appears. The goal of physical rehabilitation are as follows:

Reduce pain and identify trigger movements/positions

Provide traction (separation) to the vertebral joint where herniation occurred

Utilize movement of the spine to encourage mechanical pressure opposite of the herniation (typically this is in spinal extension)

Reduce systemic inflammation through optimized nutrition

Engage in low-intensity cardiovascular activity

Restore optimal intra-abdominal pressure and core musculature coordination

Progress movement as tolerated to return to desired activity

Re-frame negative thoughts of injury process to encourage positivity and hopefulness

Build robustness of movement and resilience to restore confidence in activity

Full return to sport

In most cases, a conservative approach that accomplishes each of the above will see the athlete make a full unencumbered recovery.

Of course we must include the disclaimer that every individual is different, every case is unique, and there is no guarantee this approach will work for everybody. But like the statistics show, this approach is more likely to work than not.

So then what happens if it doesn’t?

Surgical Intervention

Surgery for disc herniations is also relatively straightforward, and thankfully due to advancement in surgical techniques is an outpatient procedure that is minimally invasive.

A microdiscectomy is where a surgeon goes in and essentially just cuts out and removes the piece of the disc that is impinging on the nerve.

This usually results in immediate resolution of symptoms because there is no longer impingement on the nerve - that’s the good news.

But with this surgery comes other effects that must be taken into account.

As with all surgeries, physical rehabilitation must follow to ensure a full and unencumbered return to activity, especially for athletes.

This rehabilitation follows almost the exact same guidelines as the protocol for the conservative approach as written above, except this one takes into account the surgical incision and effect that has on sensation and motor patterns in the muscles of the spine.

It can be difficult post-operation to restore coordination and activation of intra-abdominal pressure as well as the muscles of posterior torso (erector spine, multifidus) making that a major goal of initial rehabilitation.

Some other common hurdles post-surgery is restoring full range of lumbar flexion as well as integrating proper lumbo-pelvic rhythm through movements. It also takes time to re-build resilience and exercise tolerance in the athlete post surgery.

In most cases with a full rehabilitation athletes can return to sport in as little as 3-6 months, or sooner if an aggressive approach is taken (with more risk of course).

Surgical vs. Non-Surgical Intervention

There is a relatively linear mental model to deciding on course of action with a diagnosed disc herniation.

If symptoms are persistent and anything more than minor an MRI should be taken to gauge the full extent of the injury.4

Radiographic images can rule out severe compressions with limited symptoms and are used to gather more information to make the best decision moving forward for that person.

A treatment plan cannot be developed based on the MRI alone, but must taken into account the human being experiencing symptoms, what their triggers are, how the injury is affecting them, and what their predisposition to other risk factors are.

In every client & athlete I’ve worked with that has dealt with lower-back pain stemming from a disc pathology, I have always recommended a conservative approach for a few reasons:

The success rate for a rehabilitative approach is high as we saw in the studies before

If the conservative approach for some reason does not resolve the injury, surgery is always an option you can keep “in your back pocket”

Once you get an operation, there is no going back. You can try a conservative approach and fail, then opting surgery. But once you get surgery you can’t go backwards. A portion of your disc has been removed, and there is no putting it back in.

You have to do the rehabilitation anyway! If you choose to get surgery, you will be doing almost the exact same rehabilitation as you would had you chose not to, except post-operation instead of pre-operation.

With that in mind, there are also other things to consider revolving the complex injury mechanisms.

We talked about how disc injuries occur and the progression - in either case rehabilitating or operating - if you don’t address the deficiencies that led to the injury in the first place even with a full recovery you will still be on the path to become injured again.

Not to mention that the number one predictor for injury is previous injury.

You must always address the root cause of injury regardless of how you decide to manage and treat it.

Recovery Outlook

This is almost entirely dependent on how well the athlete did or did not follow the guidelines above.

An athlete who took a conservative rehabilitative approach, addressed the root causes of injury so as to eliminate inefficiencies in their movement, training, and practice; will make a full recovery with little or no limitations to their performance.

The caveat here is that once you are injured there will always be a biopsychosocial influence on the injury which necessitates mindfulness, but confidence in movement is part of the recovery process and the athlete can learn to perform at a high level in their new perspective.

With surgical intervention the outlook is still quite positive, assuming that once again a proper rehabilitative program is completed and the root cause of injury is addressed.

There might be limitations in lumbar flexion and possibly rotation as down-stream effects from the surgery, but as discussed the lumbar spine is inherently not meant to rotate much anyway so that should not be a huge factor.

As it relates to golfers it goes back to the very beginning of how these injuries occur: if there is adequate hip mobility and thoracic spine mobility, they can coordinate intra-abdominal pressure, they have a proper kinematic sequence of their swing and can transmit force from the lower body to their torso efficiently through the SI joint, then it can be expected the golfer can make a full return to sport.

It must be noted here with emphasis that if at any point along this process there are weaknesses or deficiencies, the chance of re-injury increases and the limitations on their performance grows.

It may be straightforward but it is certainly not easy.

The rehabilitative journey is a mentally exhausting, physically demanding process full of ups-and-downs that will challenge the fortitude of the most elite athletes.

There are many points of possible failure along the way, and to achieve a complete resolution of injury with no lasting negative effects is hard.

But it can be done, and it can be done well.

Final Thoughts

While injuries to the spine may be a leading injury in the sport of golf, compared to other sports and activities they are only moderately common and have a low incidence rate.

The predisposition for an athlete to suffer an injury to their spine comes from the efficiency of their movement in repetitive motions (such as the swing), as well as their ability to coordinate musculoskeletal movement in a way that transmits force efficiently.

Lack of prerequisite strength, mobility, and coordination all increase the risk factors for sustaining a back injury.

How the athlete progresses their practice and training is also a leading indicator for experiencing back pain and their overall experience and resilience to physical activity plays a large part.

If an athlete does sustain a disc injury, a conservative rehabilitative approach should always be tried first, opting only for surgical intervention if ineffective. In both cases long-term outlook is very positive assuming a proper rehabilitation is followed in its entirety.

Don’t be scared of injuring your spine if you play golf.

Take care to learn proper technique both in the swing and in the gym, place an emphasis on mobility in the hips and thoracic spine, learn how to create intra-abdominal pressure through the coordination of breathing and abdominal muscles, and progress the intensity of your training and practice slowly with respective to your improvement.

Do these things and you will be able to play golf at a high level, for a long time!

If you have questions on any of the information presented here, please ask in the comments!

Note: Any questions relating to your personal situation cannot be answered. If you are having back pain seek out a qualified medical professional.

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice. The content is purely educational in nature and should be filtered through ones own lens of common sense and applicability.

A key note here is that images are not a diagnosis. If we MRI’d 100 people a good percentage would display some progression of “herniation” but be asymptotic. Images are used to add context and information to a clinical assessment based on pain, limitations, and symptoms. They should not be used as in absolute to make treatment decisions.