Effective Practice for Skill Acquisition

Level 4: All-Star

Welcome Players! At the foundation of every elite athlete is elite levels of skill. While physical ability sets the stage for the performance, the skill of the game is ultimately what separates the winners from the losers. In this article we reveal how to construct the best practice environment to promote efficient and permanent skill acquisition.

Contents:

The Warm-Up

What Defines Successful Practice

Learning in Skill Acquisition

Contextual Interference

Types of Practice

Role of the Practicer

Creating an Effective Practice Environment

Final Notes

The Warm-Up

Yes. That’s Allen Iverson asking, “How the hell can I make my teammates better by practicing?!”

Well AI, I can’t speak for your teammates but I’m going to tell you exactly how you can improve your abilities through practice and how to most effectively practice for improved performance when it matters. In the game.

You see practice isn’t just the idea of repeating motions that are going to be performed during competition. It’s much more than that.

The purpose of practice is to challenge your abilities in a controlled environment that leads to an improvement in performance.

Practice too little / too easily and performance will decrease or plateau.

Practice too much / too intensely and performance will decrease or plateau.

Practice the wrong things and performance will decrease or plateau.

Practice the right things in the wrong environment and performance will decrease or plateau.

Practice the right things in the right environment for the right amount of time and performance will improve!

Conditions for Effective Practice:

Practice organization must match the experience and skill level of the participant

The skill being practiced must involve unique problem-solving tasks

The tasks must include sufficiently different variations of the skill when performed within the same motor program, or be made up of an entirely alternate motor program all together

The level of cognitive interference must be high relative to the individual for optimal retention and transfer

Practice structure progresses from block, to variable, to mixed, to random sequence of tasks

The individual must engage in deliberate practice

The attentional focus of the individual flows from internal as a beginner to distally external as an advanced practitioner

There must be a period of time between practices that allows for the processes of learning to take place (mainly during sleep)

Do all these things and science has proven you will be in an optimal environment for learning a new motor-skill. With enough time, consistency, dedication and effort you will have all the odds in your favor of competing at a high level!

What Defines Successful Practice

Let’s look at what practice should be:

The effectiveness of a practice condition should only be evaluated in terms of its influence on being able to reproduce the practiced skill at some later time following a period of no practice (i.e., retention), or to successfully perform a novel variation of the practiced skill (i.e., transfer).1

Practice for the sake of practice is useless.

The goal of every practice session should be to reproduce the skill being practiced at the time of competition better than before.

The goal of practice is to improve.

Let’s narrow our discussion a bit and specifically talk about practice in the context of developing a motor skill.

This could be something like a golf shot, where the goal is to hit the ball into the cup in as few strokes as possible, it’s necessary to move the body in such a way that creates a swinging motion of the club.

It could also be a basketball jump shot, where the body has to jump, control itself in space, and launch a ball at a basket in hopes of scoring points. The skill here is getting buckets, the motor skill is the jump shot.

If the goal of practice is to improve skill, then what defines a motor skill?

The ability to throw a baseball at high velocities to a small target repeatedly is the skill of a professional baseball pitcher. What we’re going to talk about specifically is the influence of practice on that pitcher’s skill - or his ability to organize movement in a manner to deliver a throw that results in a strike.

In this sense when we talk about skill we’re actually concerned with the act in which a human nervous system learns motor patterns.

If you’re trying to practice effectively you’re trying to teach your body how to perform a movement in a better manner. Better being subjective to the goal of the task at hand.

While some pitchers may try to increase their pitch velocity, others might work on increasing the variety of their pitches (curveball, slider, etc). Both are practicing a specific task that they hope will transfer into improved performance on the baseball field.

We must address here that although we’re going to funnel this exploration of practice in specific terms of optimizing motor learning, improvement in task-completion is multi-factorial and complex.

The experience of the individual, exposure to previous environments, personal beliefs, emotions, and perceptive context of performance all matter when analyzing an individuals propensity to perform. These things in turn will also affect their practice.

Learning in Skill Acquisition

Fostering learning is to keep a delicate balance between providing tasks that are more challenging than the individuals current ability yet are not so difficult as to incur negative results.

Tasks are science-talk for literally any requested thing that is to be completed.

Shooting a basketball is a task.

Hitting a golf ball is a task.

They can be broken down into smaller or larger components as well.

Shooting a step-back three-pointer is a more complex task than shooting a free-throw.

Hitting a full-swing driver into the fairway is a more difficult task than hitting a 9i lay-up.

Tasks are set ahead of time to provide clearly defined rules and parameters for what is being asked of the performer.

You might see basketball athlete practice a drill by standing two feet in front of the rim and shooting the basketball into the net with just a pronounced flick of the wrist.

This is the task of that practice drill. The goal is to practice that task so that it transfers into other skills that require that include more complex movements, such as a jump-shot.

If by practicing the release of the wrist in the drill it leads to improved performance in jump-shots by way of transfer of skill, then that is considered to be a successful practice drill!

So what determines the efficacy of any individual task as it relates to practice?

Research has shown that it’s not just the act of repetition that encourages improvement in skill.

Repetition serves as the vehicle for which motor-learning can take place.

How you perform a repetition, what the task of that repetition is, how that task relates to goals of performance and the sequence or structure of this practice are all vitally important to getting the most out of your efforts.

In order for a task or repetition to be beneficial in a practice setting it must stimulate a certain amount of cognitive processing.

We can think of learning as the completion of a series of problem-solving tasks.

Every novel task that our brain is required to find a solution for requires a certain level of cognitive effort.

The easier the problem is to solve, the lower the effort. Likewise the more difficult the problem is to solve, the higher the effort.

If a task is too easily solved, or worse has already been solved through repetition, then it will no longer require enough cognitive processing to be beneficial and could even bypass all mental effort altogether.

This is detrimental for skill acquisition as the brain is either learning or forgetting; no in between.

In our example before of the basketball player shooting mini-shots with just the flick of the wrist; if said basketball player has done that drill a thousand times it likely is not contributing to improved performance at all. The players’ brain has performed the skill so many times that it no longer needs to expend energy to problem-solve the task. It is now simply repeating the motion without contributing the mental stimulation necessary to retain that skill after a period of time.

While you may be tempted to think that the repetition improves “muscle memory” and is contributing to the ability to perform that skill in the game, decades of psychological and neurological research says otherwise. It’s likely not contributing to improve their performance in a game.

Repetition therefore should not be defined by repeating of a movement or pattern but by the determinant of whether or not a problem was solved (both cognitively and motor wise).

Repeating a task (repetitions) that don’t require the brain to solve a novel problem inherently contribute less to improvement in skill than tasks that do require problem-solving effort.

The process of practice towards the achievement of new motor habits essentially consists in the gradual success of a search for optimal motor solutions to the appropriate problems. Because of this, practice, when properly undertaken, does not consist in repeating the means of solution of a motor problem time after time, but in the act of solving this problem again and again by techniques which we changed and perfected from repetition to repetition. It is already apparent here that, in many cases, "practice is a particular type of repetition without repetition" and that motor training, if this position is ignored, is merely mechanical repetition by rote, a method which has been discredited in pedagogy for some time. - Nikolai Bernstein2

Effective practice means solving unique problems to accomplish a goal. How unique does the problem have to be in order to benefit? Let’s find out.

Contextual Interference

It is surprisingly difficult to objectively measure how effective a certain type of practice is for improving performance.

Science has landed on two main ways to gauge improvements in motor learning. They are tests of:

Retention: a test of ability performed after a period of time following the end of practice.

Transfer: a test of ability similar to but slightly different than the one that was practiced.

Without these two types of evaluations we can only empirically compare the performance on a practice test at time A with performance on the practice test at time B. It is almost impossible to conclude whether the practice session contributed to a permanent or otherwise significant increase in skill or simply improved the individuals ability to perform at that test over time.

How likely is a task to contribute to retention and transfer of skill?

Well that comes back to the cognitive effort spent on problem-solving to complete that particular task.

If the task is a novel stimulus, meaning the individual hasn’t done it before and therefore has to “figure it out” in order to succeed, they are likely to see significant improvements in the retention and transfer of that skill on follow-up evaluations.

If the task is not a novel stimulus, where the individual has been exposed to that task previously and already knows how to successfully complete it (meaning no problem-solving ability was required), then they are likely to see less improvements in the retention and transfer of that skill.

The only caveat is that in the context of a novel stimulus where the individual undergoes a high-level of cognitive processing, they are expected to perform worse during the practice session. Likewise for non-novel practice stimuli the individual can be expected to perform better during the practice session.

This phenomena is defined as cognitive interference:

Practice situations in which performance of one activity results in a performance detriment for another activity but paradoxically leads to better learning.

This proven concept says that in order to improve learning outcomes in motor-learning tasks the practice environment should be one in which enough levels of cognitive processing are required paradoxically resulting in negative acute effects in performance.

Contrary to our intuition which leads us to believe that in order to actually get better from practice, we should be getting better at practice.

Not true!

We can use cognitive interference as a way to delineate the difference between low- and high-effort cognitive processing during a task.

If a task is familiar and requires no novel problem-solving stimulus, it is said to have low cognitive interference.

If a task is unique or novel and requires problem-solving, it is said to have high cognitive interference.

Let’s summarize what we know about practice:

Practice is the act of working to perform a particular task at a unspecified time in the future at an ability level equal to or above that of previous attempts

A task is a particular movement or event that is required to achieve a goal

Skill, in our definition, is the ability to successfully complete a task

We can improve skill by way of enhanced motor-learning in the pathways of the nervous system

In order to have positive motor-learning effects while undergoing practice, the task being completed must provoke sufficient levels of cognitive processing and problem-solving

A repetition is not the repetitive act of completing a motion, but the repetitive act of solving a unique problem through the completion of novel tasks

Practice that has low levels of cognitive interference will improve practice performance at that practice but will not improve skill retention or transfer significantly

Practice that has high levels of cognitive interference will decrease practice performance at that practice but will improve skill retention and transfer

As we talk about the influence of cognitive effort on effective practice it’s also important to understand the scientific concept of general motor programs.

A general motor program refers to the neurological wiring that occurs in order to coordinate stimulation of thousands of muscle fibers at the right time and in the right sequence to produce a desired movement outcome.

We can think of a general motor program as the brain ‘batching’ individual movements into one larger movement in order to save processing time.

For example, in order to kick a soccer ball, the brain must first learn how to balance on one leg while extending the other leg in preparation for the kick, and then balance shifts in momentum to swing the other leg accurately to contact the ball with the foot in the precise manner so as to deliver the soccer ball with enough force to kick it where you intended it to go. While we can break this process into infinitely small pieces, this is the gist.

Once the brain solves for this movement problem enough times, it can group each of these finely-controlled individual movements into one large action: a kick.

Once the nervous system has an engram of a movement it saves an incredible amount of cognitive processing to focus on other aspects of the task, such as the velocity of the kick or kicking the ball to a small target in the goal.

The neurological formation of general motor programs and their execution within the nervous system are a powerful concept when trying to improve motor learning.

They are important in this context because whether or not a task replicates the motor program of the skill being practiced has a large affect on the level of contextual interference that task incurs.

There are two outcomes depending on similarity of task to skill performance during practice:

If the task being practiced utilizes an entirely different motor program than the skill requires, then that task has high contextual interference.

If the task being practiced is within the same motor program as the skill but is performed with different parameters, it either eliminates contextual interference altogether or significantly reduces it.

Here’s an example of two scenarios where your goal is to improve your skill of hitting an accurate tennis forehand.

In the first you complete the task of hitting two-handed forehand shots in practice. This uses a different set of muscle activations in the swing, and thus a different general motor program is being used. It’s considered high interference because the cognitive processing required to complete a different movement pattern is greater than just modifying a piece of an existing pattern, such as hitting a forehand strike but at a slower speed.

While these examples may be made in black & white, the reality is that contextual interference occurs along a continuum that may be different based on each unique individual and environment.

If you are practicing a similar task with multiple variations the processing requirement is low = low interference.

The more modifications you make available while still in the same motor program and thus high-similarity to the skill being tested the closer you’ll get towards finding the contextual interference effect.

Let’s look at an example of contextual interference that changes based on the experience and skill level of the individual practicing:

Specifically we’re going to look at a golfer practicing shot shapes with a 7i. The general motor program in this movement is swinging a golf club (7i). Let’s say we want to practice hitting draws and fades. The difference in movement between hitting a draw and a fade is very subtle in relation to the change in swing when hitting a 7i vs. a lob-wedge. This means draw-patterned swings and fade-patterned swings are low contextual interference in relation to our practice.

If we wanted to practice our skill effectively by increasing the cognitive demand we would have to either continue to change parameters until we are far enough away from the general motor program (changing shot types) or change the general motor program altogether (hitting with wedge).

This means if we want to change our pattern enough to make the next swing stimulus unique, we might have to do something completely different first!

Each individual will have to find where they sit along the spectrum of contextual interference and continually adjust their practice relative to their experience in order to encourage problem-solving within the task.

The more difficult the learning situation the more effort will be applied towards problem-solving will lead to greatest contextual interference and thus highest retention & transfer results.

Types of Practice

The most effective way to increase contextual interference and thus improve retention and transfer of skill is to manipulate the organizational structure of your practice.

The following are the main types of practice structure as it relates to skill acquisition:

Block practice: repeating a task of the same goal until all repetitions are complete

Variable practice: repeating a similar task of the same goal with different parameters

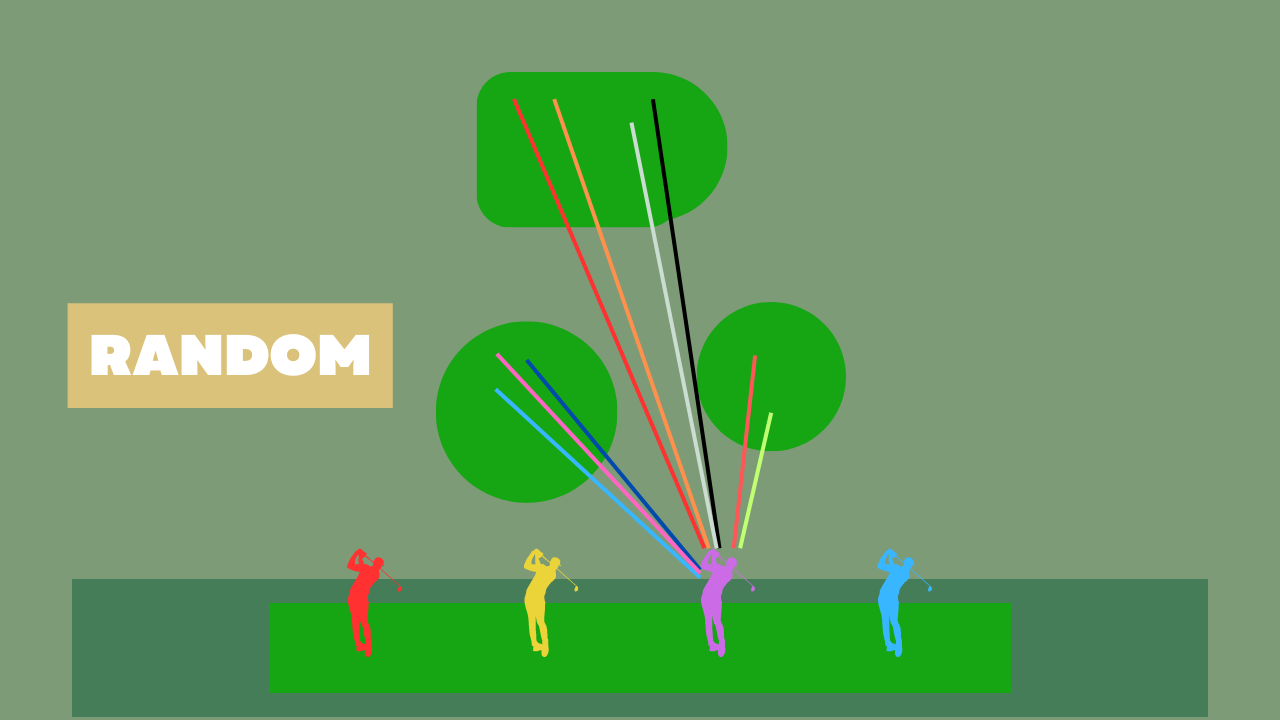

Random practice: practicing different tasks with respective goals in random sequences

Mixed practice: a combination in any manner of block, variable, and random practice

Each form of practice holds its value at different times depending on the individual, the environment, and the goal.

Block practice results in better performance of the skill during that practice period and at the end of that practice but does not significantly improve skill retention or transfer.

Random practice results in worse performance of the skill during that practice period but improves retention and transfer of that skill.

Mixed practice is shown to be highly effective for beginners because a high-contextual interference practice environment may incur too high of a processing difficulty to encourage optimal learning.

There is likely a gradient of experience that mixes with individual differences in capabilities where the benefits of low vs. high contextual interference are altered.

For beginners it is ideal to utilize block practice that is focused on getting the idea of what is required from the task and allows for problem-solving to take place.3

When a measure of comfortability with the task is reached it’s then better to switch to a higher-contextual interference environment like random practice to then develop proficiency in movement solutions.

If the target task requires use of different motor programs, then high-interference random practice produced improved retention and transfer rates. However, if target task only requires variations of same motor program, than it’s likely early block practice followed by later random practice is most beneficial compared to either alone.

There is one more form of practice that can be of great benefit provided the core of your practice is made up of the concepts above.

That is the practice of observational learning.

Just as it sounds, observational learning is the act of watching someone else perform the task or skill you’re trying to learn and becoming better from it.

Of course there are a host of conditional factors that must be true in order for observational learning to be as beneficial as you might think.

All else aside, observational learning benefits most the individual who is already partaking in their own structured practice regiment. It will not have nearly the same effects on someone who is not actively practicing. So no, watching is not as good as doing.

If you are practicing consistently and looking to add another form of learning to your arsenal, observational practice provides a great opportunity. It allows for neurological repetitions when the physical body cannot perform. It also allows for a vast increase in contextual exposure to the task being performed. We can watch significantly more unique scenarios than we could actually experience those unique scenarios in the same amount of time. The power of the internet!

Another way to leverage your observational learning is by altering the skill level of what you’re watching.

You might be tempted to think that this means you should watch the best of the best at your skill and learn from them. But once again our intuition leads us astray.

Watching someone who is already proficient at the skill we’re trying to learn is beneficial.

But watching someone who is not proficient at the skill we’re trying to learn is even more beneficial.

This is because when you are watching a professional you are watching them perform, not problem-solve. Remember that all the magic of repetition is in stimulating the nervous system to problem-solve for a goal-based task.

By watching let’s say an amateur practice the skill, you’ll be watching them make far more mistakes than a professional. Which is a good thing! You can experience the problem-solving stimulation from watching them make and then subsequently try to fix their own mistakes at a much higher level than you would should a professional do that.

You’re learning through the problem-solving efficiency of their repetitions, not just the completion of the task.

With the concepts of motor-learning, skill, and practice structure all in place there’s just one final piece of the environment to optimize before building a perfect practice: You.

Role of the Practicer

Up until this point we’ve talked almost exclusively about the external environment as it relates to practice. The conditions, tasks, skills, goals, structure, etc.

The final piece before we can construct the best practice environment for skill development is to align our internal environment.

The first way we do this is by being intentional through deliberate practice:

effortful in nature, with the main goal of personal improvement of performance rather than enjoyment, and is often performed without immediate reward4

There are a few key ingredients to deliberate practice:

Task has a well-defined goal

Individual is motivated to improve

Feedback is received

Provided with ample opportunities for repetition and refinements

The difference between practicing just to practice and practicing to improve are worlds apart. The former leads to burnout, plateau’s, and discontent. The latter leads to validation, improvement, and accomplishment.

Deliberate practice also has a profound effect on contextual interference in that when you are truly focused on a task you are inherently investing significant cognitive processing to problem-solving tasks. Having a high capacity for mental effort and then challenging that potential for effort in the appropriate manner is a recipe for great success.

The second internal factor that contributes to an elevated level of practice for performance is attentional focus:5

what you concentrate on when performing a movement or activity

There are four types of attentional focus:

Broad

Narrow

External focus

Internal focus

We’re mainly going to be using the last two: Internal and External focus. When you focus internally, you’re trying to consciously control your body based on what you feel. You move your arm to purposefully position your hand on the mouse.

External focus is when you are focusing on an object or area outside your body. You want to subscribe to this substack so you manipulate the cursor into clicking the button. Your arm moves to create this action without thinking about it.

This study looked at which would be better for performance of low-handicap golfers and found that focusing on ball flight (distal external focus) produced better results in a 20-yd pitch-shot than focusing on club face (proximal external focus) which both produced better results than focusing on movement of the arms (internal focus).

An important factor of deliberate practice can be added here in that attentional focus should be directed externally and distally for best results on skilled performance.

One distinction is that for beginners it might be better to actually start with an internal focus until some semblance of patterning is formed and then refine it as attentional focus flows outwards. This is similar to concepts of block practice for beginners in practice structure and then transitioning into random or variable practice as they develop repeatability.

Creating an Effective Practice Environment

Practice structure and modalities will differ respective to the experience and skill level of the individual participating.

We can drop participants in skill buckets of Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced and Expert.

Beginners

Beginners undertaking a new skill practice should decidedly spend their time and effort on building a foundation, not advancing their skill. They will be experiencing novel movement and stimulus for a repeated movement and will need time to adapt positively.

It is much more probable to make a beginners path more difficult by engaging in advanced practices or techniques than it is to quicken their efforts. It takes time for the neural networks that coordinate movement to develop and no amount of mental effort will change that.

The goal in a beginner is to create a positive environment to encourage learning.6

This includes things such as establishing the habits, attitude, effort, and schedule that can serve as the foundation for learning once the neurological system responsible for movement has been primed.

Practice should be oriented in a form of large-batch variable blocks, adjusting to spend no more time on each block as attention lasts. Feedback should be based on performance independent of result and should call attention internally to influence movement decisions.

Skill to be developed: Archery

Task to be practiced: Making contact with target at 10m distance

Practice structure: Block-Variable. Shoot 10 arrows in a row per set

Cognitive interference: Low. Alternate task distance by 2m every set

Attentional focus: Internal. Focus on establishing proper technical form via positioning of the body.

There should be care not to over-instruct or over-emphasize small details.

We can lean on a constraints-led perspective of learning that indicates that once a goal for a performer has been specified, then a process of random exploration eventually results in a solution to the task given any constrains placed upon them.7

The performer needs to be given enough space to allow for natural discovery of accomplishing the goal. This leads to the most effective type of learning and when fostered appropriately holds the highest potential for skill mastery.

Practice time should begin to scale along with the beginner’s interest and capability. When you’re just starting out forced practice can significantly hinder your natural development. Allow yourself to become interested in the skill and seek ways to improve your ability naturally before seeking pre-solved solutions. While you may end up in the same place eventually, discovering the errors for yourself allows for a greater potential throughout growth.

Intermediate

As soon as the beginner shows signs of a routine habit in the skilled movement they are ready to be progressively challenged.

With a positive environment in place it ensures no negative influences can arise from practice except those naturally occurring in practice.

Practice types changes from a rigid variable-block repetition to one much more dynamic utilizing a mixed method: some block, some variable, some random, assigned either in order or in a preferred order. Drills are progressed to increase in cognitive interference through more difficult problem-solving tasks and retention of ability.

Movement habits and patterns begin to take shape and performance improves.

Skill to be developed: Archery

Task to be practiced: Hitting target within point-scoring rings

Practice structure: Mixed. Begin with block practice of 15 arrows in a row per set with goal of scoring points on target. After 3 sets at variable distances, change to variable practice alternating distance every 3 shots in either a random or pre-determined sequence. Do not repeat sequence more than two consecutive sets.

Cognitive interference: Higher than in Beginner due to mixed practice structure. If successfully scoring points every shot, narrow task-goal to include specific ring to target. Randomly assign new target-ring every 3 shots.

Attentional focus: External Proximal. Focus on positioning of the bow.

Advanced

After enough deliberate practice and progressive structure advanced skill will be achieved. Practices become mainly constructed out of objective-based games than nurture advanced techniques or concepts. They are not repetitive in similarity and encourage competition. Focus is almost excessively on an external object the determines performance in the task.

For skill sports success at the advanced level is often less physical in nature than it is strategical. Advanced skill allows for a dynamic gameplay that can accommodate for strengths and weaknesses appropriately. The best golfers can play at any course in the world at the highest level with predictable success. Some amateurs are home-town heroes for a reason.

Practice must be continuously designed in a way where cognitive interference is high enough to challenge problem-solving. Some people can have a difficult time challenging themselves in a way that promotes growth, not burn-out.

Skill to be developed: Archery

Task to be practiced: Scoring max amount of points per shot.

Practice structure: Random. Create mini-games that are reflective of performance at the task. Every shot is randomly selected to be from a different distance within a dynamic environment.

Cognitive interference: High. Frequently change parameters and contextual environment to challenge cognitive processing. Play disruptive sounds during shots. Re-position the target. Include (non-living) decoys or barriers to interrupt line of sight.

Attentional focus: External Distal. Focus on flight of arrow.

While as difficult it is to develop advanced skill level, even more so is it to achieve the title of expert.

Expert

Skill mastery. Some say it doesn’t exist. The philosophy of mastery of any skill is a fascinating one.

Floyd Mayweather Jr. is an expert boxer. Marc-Andre Leclerc was an expert alpinist. Tiger Woods is an expert golfer.

You don’t need me to tell you what defines an expert at a skill. You’ll know it when you see it, and if you’re not sure they’ll certainly be able to demonstrate.

It’s difficult to talk about the way experts are “supposed” to practice. At that level so much of it becomes individual environment and contexts that it’s hard to extrapolate conditions to other similar ones. Some great athletes like Michael Jordan practiced ferociously throughout his entire career, while some like Tom Brady practiced differently.

Less focus on the performance of the skill through repetition and more focused on refining strategical outcomes as it relates to that skill. Veteran soccer players report the game ‘slowing down’ when in reality their game-IQ and pattern recognition is developed to a point where their reactions are able to process significantly quicker than someone just experiencing those patterns for the first time.

This can cover a large gap in physical prowess and is a definitive result of expert skill practice. Especially over long enough career where physical abilities wane in suit of biology, skill acquisition and development can serve far longer and more advantageous than most physical abilities.

Skill to be developed: Archery

Task to be practiced: Scoring from strategically advantageous or dis-advantageous positions that are likely to occur in competition.

Practice structure: Random. Assign unique scenarios for every shot that include context and changes to the external environment. Mentally commit to a competition atmosphere and re-create the necessary shot for victory in the prescribed scenario.

Cognitive interference: High. Create novel scenarios that may not occur in competition but require skills or attributes that can add value to performance.

Attentional focus: External Distal. Focus on trajectory of arrow with respect to environment. Wind, temperature, humidity, etc.

Final Notes

Practice to improve.

Regardless of where you’re at in your skill development journey, one common theme that can be found across the entire spectrum is the intention to improve.

When you set out with the goal of improving at a skill, and you practice, make errors, and then learn from those errors you are participating in an extremely unique experience to the nervous system. It stimulates growth, positivity, and new perspectives.

Nurturing your body to learn a new skill is like adding to a piece of yourself. The things you’ll learn throughout the dedicated practice will come to shape and form some of your views. It will alter your perspective for better or worse and that will become a part of you.

These experiences become less and less frequent in life. As kids we were bombarded with opportunities of growth and throughout adulthood they become less available - in seniority they can even cease, signaling severe loss of happiness.

The journey is more important than the destination rings true on not just a philosophical level but on a biological one as well. The value is in the process of creating these neural pathways, not in the end-result of them being there. Take expert skill out of one person and drop it in another with no context of the acquisition of that skill and they’ll be no happier than before!

So if you’re not already practicing something, allow this to be my encouragement to do so.

It doesn’t have to be a physical skill, or a performative skill, or competitive skill at all.

It can be something artistic like drawing, or creative like photography; musical like an instrument; expressive like dance. It can be athletic like golf or basketball. It can be something no one else in the world cares about. As long as you do.

The freedom to select what we want to be good at is as powerful a feeling as you can experience. It’s a way to align your lifestyle with what your goals and take back control of how you pursue both.

When you set-out on your journey I hope this information helps you find a structure that advances your pursuit and compliments your goals.

May your practice result in all the improvement you plan for!

Have a question? Want to share your experience with us so others can learn too?

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice. The content is purely educational in nature and should be filtered through ones own lens of common sense and applicability.