Welcome Players! Last week we went in-depth on Heart Rate Variability: what it is, how it’s measured, what those measurements mean, and how it all relates to stress. If you haven’t read it yet, you can catch up here. This week we’ll be building upon that knowledge to discuss how lifestyle choices and activities influence HRV, why they may have that affect, and how you can use that information to improve not only how you feel & live, but how you perform in the the activities that matter most to you.Let’s go!

Contents:

The Life You Live

Effects of:

Age/Gender

Stress

Physical activity

Resistance training

Diet/nutrition

Sleep

Substances

Internet addiction (yes, addiction)

Why it Matters

Long term change vs. Short term improvement

The Life You Live

Far too often it is easy to overlook how our daily habits shape the outcome of our future. Examples can be seen in all aspects of life; how you eat will reflect in your physical appearance; your levels of physical activity will determine your fitness ability; how your parents raised you influences how you will raise your children, etc.

Your long-term habits will have the greatest impact on your health, bar none. You can use all the short-term optimization techniques you want, but if you put them on top of bad habits you will be going nowhere fast. I wrote about this concept here, explaining why you should set up your life and habits around the goals you want to reach to be sustainable and effective.

All this to say that I know you want to learn what things you can do to train or optimize your HRV, and you expect those things to be specific protocols or interventions. You need to recognize that is a bias you hold. There are no shortcuts in health and performance; stop trying to find them, because you will chase them for the rest of your life.

The things I’m going to be talking about in this article are simple, almost too simple, things that will have a far greater return than any specific intervention will. And we’ll get to the interventions (next week), but if you are truly serious about improving your quality of life you’ll heed these words and take action immediately to build a sustainable lifestyle through daily habits and consistency. Let’s go!

Effects Of:

Many of the studies I’ll be referencing (you can click on footnote to be taken to a link to the source) are retrospective studies that evaluate HRV parameters in different cohorts of populations. While this isn’t the most specific way to perform an experiment (vs. an A/B test & control) it does provide us with a glimpse into the effects across a large population.

These studies are valuable for us because we want to know what general trends and correlations are between different lifestyles and habits and analyze them across a large population. We’ll start with genetics for context on comparing numbers to ‘norms’, then moving to explore how things you do everyday impact your HRV.

Age

The older you get, the lower your HRV is.

And a lower HRV is a bad thing. We can use HRV as an indicator of vagal influence on the heart, which you’ll recall is akin to saying that the ability for the body to be influenced by the balance of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system is an indicator of long-term heart health. As you get older, the natural aging process begins to wane your bodies ability to rev up the engine and cool it off again. This can be seen as a reflection of various HRV metrics, which we’ll look at two very important ones: LF (low-frequency) and SDNN (standard deviation of normal R-R intervals).

Coaches note: there are more metrics that factor into the association between the autonomic nervous system & health, I have chosen to highlight these two for simplicity and comprehension

In this study:

60-69 year old male LF = 573ms^2 +/- 207

20-29 year old male LF = 2034ms^2 +/- 950

A huge difference! And if we look at SDNN:

60-69 year old male SDNN = 156ms^2 +/- 31

20-29 year old male SDNN = 187ms^2 +/- 40

"Our results confirm that older age is associated with a decline in vagal modulation of heart rate, as reflected by a significant reduction in parasympathetically mediated indexes of HRV (rMSSD, pNN50, log [HF power])."

Utilizing metrics such as these we can accurately relate the changes in HRV as we age to indicate overall cardio metabolic heart health. This should be no surprise since we know that HRV metrics & the R-R interval can be used as a predictor for a cardiac event (stroke, heart attack, etc) and chronic heart-disease.

There’s nothing you can do about getting older. It’s the natural progress of life. But what you can do to attenuate the effects of aging on your heart health is be mindful that how you spend your energy as you age, will in large part determine how much energy you have left to spend in that age!

Coaches note: If you’re getting confused with the HRV metrics and what they mean, then I’ll suggest you catch up by reading our previous article that explains them in full here.

Gender

Not much to be influenced here, but it’s interesting to note so will include it for informational purposes.

Women tend to have naturally lower HRV’s when compared to age-controlled men. Women also tend to see less reductions in long-term indices of HRV as they age compared to men, instead showing only significant decline in short-term indices. So while they may not achieve as great an absolute HRV as men, research indicates the heart in females is slightly buffered against declines throughout the aging process.1

This is useful to know so that if you are comparing your HRV to a ‘standard’ or group, you should do your best to find age- and gender- controlled norms.

Physical Activity

I’ll prelude this category by saying that it’s very difficult to associate a % change in HRV as a result from an exercise intervention in the scientific literature. You’d have to control for a ton of lifestyle factors in age and gender matched groups along with a control, in an experimental design just isn’t feasible without massive amounts of funding and subject commitment. So, you won’t see any statements such as “Exercise for X time/intensity = Y improvements in HRV! Just do that!”. No. That’s not how it works.

Resistance Training

In two different studies resistance training was found to have no effect on resting HRV in healthy young adults, one for a 6-week intervention and one for an 8-week intervention. Even in older women (~70 years old), resistance training for 6 months found no significant change in HRV. 2

What’s interesting is that in healthy populations there was no change, but for individuals who have some form of autonomic dysfunction (like fibromyalgia) there was an increase in overall HRV after four months of resistance training. This likely has to do with the autonomic stimulation from training having a greater effect on someone with a compromised nervous system than it does in healthy populations. 3

Interval Training

Because HRV can be thought of as the body’s ability to get high (in heart rate) and get low (also in heart rate), interval training makes a lot of intuitive sense as to why it would have positive affects on HRV as a result.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) showed the greatest improvement in HRV and sympathovagal tone compared to medium-intensity continuous training (MICT). Although MICT did not show the same improvement in sympathovagal activity. 4

Sympathovagal is a term to describe the interaction between the sympathetic nervous system and the vagus nerve, which is linked to parasympathetic influence ie. one perspective of the balance between the two

Some things to note for the parameters in the above study:

Exercise was tested on a cycle ergometer with light resistance

HIIT = 20min of 10s work w/ 50s rest at >/= 90% of HR peak

MICT = 40 min of continuous cycling at 60-75% HR Peak

Both groups completed 8 sessions in 2 weeks, groups contained physically inactive adults

This is clear as day. If you want to make the most improvement to your cardiac health as measured by HRV you should be opting for 3-4 sessions a week of HIIT training. The good thing about this approach is it doesn’t take a lot of time! 30 min from warm-up to cool down should be enough to elicit positive adaptations if you’re just getting started.

Don’t like going to the gym? Fine, don’t! But you need to find an activity that elevates your heart rate. You will not be able to improve your HRV significantly if you do not push your HR to near-peak levels. Walking is a great activity for combatting sedentariness, but it won’t make an impact on your HRV. A simple change would be to intersperse 5 min of walking with 1 min of running/sprinting. Wah-lah, interval training accomplished! Don’t make it complicated, elevate your heart rate while working really hard for a short amount of time, and then rest or perform some form of low-intensity activity in the recovery period. Do this often!

Nutrition/Diet

Similar to exercise, this is another area where proven scientific guidelines will be very difficult to find. The studies I did come across were exploratory in nature but did manage to find some correlations that align very much with nutrition guidelines for a healthy heart independent of HRV, but again, common sense can take you much further than the research here.

Because of the lack of sufficient evidence, I’ll keep this brief:

In a cross-sectional study evaluating the relationship of lifestyle, dietary patterns, and anthropometrics: 5

Higher fruit consumption had a significant impact in the improvement of HRV

Higher fat adiposity (as measured by body fat %) related to lower HRV

Higher intake of refined grains & simple sugars had an impact on cardiac risk which was presumed (not proven!) to effect HRV negatively

Supplementation of OMEGA-3 had a beneficial effect on cardiac health, also presumed (not proven!) to positively impact HRV

There’s not much groundbreaking info here. If we continue on the basis that dietary choices made to improve cardiac health can/will also improve HRV via the mediation of electrical activity of the heart, we can follow basic guidelines that include limiting processed food, eating full recommended amounts of whole fruits & vegetables, and ensuring adequate protein intake to match our cardio metabolic needs.

Sleep

I’ve written at length about the necessity of getting sufficient amounts of quality sleep. You can read about it here and here.

If you’ve read those then this should come as no surprise to you that receiving full sleep hours (>/= 8) has a significant positive correlation with HRV, where longer sleep times are associated with a higher HRV. 6

It was also shown that chronic sleep deprivation reduces the body’s ability to regulate balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, causing a net decrease in HRV indices. 7

More ammo to prioritize sleep, compounded here with the potential effects on cardiac health and HRV in addition to all the physical and mental components talked about in prior articles.

Substances

There’s not much research here either, but it’s worth to note the two most popular substances in the world both display evidence of negative impact to HRV.

Alcohol

“…we have reported evidence indicating that alcohol dependent patients (n = 177) relative to healthy, non-dependent controls (n = 216) display reductions in HRV, and that these findings are not due to cardiovascular disease or comorbid psychiatric illness.” 8

“HRV reduces with the acute ingestion of alcohol, suggesting sympathetic activation and/or parasympathetic withdrawal. Malpas et al. have demonstrated vagal neuropathy in men with chronic alcohol dependence using 24 h HRV analysis.” 9

Smoking (tobacco)

“Studies have shown that smokers have increased sympathetic and reduced vagal activity as measured by HRV analysis. Smoking reduces the HRV.” 10

You will be hard pressed to find any positive physiologically or biological effects of alcohol and tobacco. This is not to pass judgement on those who use them, but we must confront science with the facts, not our bias.

Emotions

Yup, that’s right, your emotional and psychologically state can have impacts on your HRV. How you think/feel sets a primal response from your nervous system to sway in a unilateral direction towards either fight/flight or rest/digest.

Studies have looked at opposite emotions and their respective affect on cardio metabolic responses through HRV metrics. Most notably the comparison of anger vs. gratitude. It was shown that study participants who experienced feelings of anger increased sympathetic activity, while experiencing feelings of appreciation increases HF values, indicative of increases in parasympathetic activity.

If this was a psychology-based educational article we could fully vet the effect emotions have on our physiologically responses. Unfortunately it is not, so I’ll leave you with this: positive emotions such as gratitude and appreciation on a biological level promote expression of the parasympathetic nervous system, allowing maximizing of our HRV and feelings of a calm, balanced state. Negative emotions increase expression of our sympathetic nervous system, reducing HRV metrics and further enhancing feelings of stress. 11

Internet Addiction

This was one that I did not expect to come across in my probe of the research, but I couldn’t leave out once I read it.

This study looked at internet use in students aged 10-15 in Taiwan. They classified ‘internet addiction’ as > 38hrs of internet use per week (~5.4hrs/day), and found that:

“Through HRV testing, our results suggest that school-aged children with Internet addiction have higher sympathetic activity and lower parasympathetic activity and overall autonomic activity.” 12

It’s very interesting that for as much as we know that prolonged use of technology/devices negatively impacts our psychological well-being, objective HRV data also indicates the harmful effect it can have on our cardiac and autonomic nervous system balance. As I sit here typing on 2 computers, and you read on a device, it makes you wonder how sustainable this practice is? A post for another day, perhaps…

Take a Deep Breath!

That was a lot. We took a comprehensive look at many common lifestyle habits and how they affect our HRV, for better or worse.

Hopefully now you can answer this:

Why does it matter?

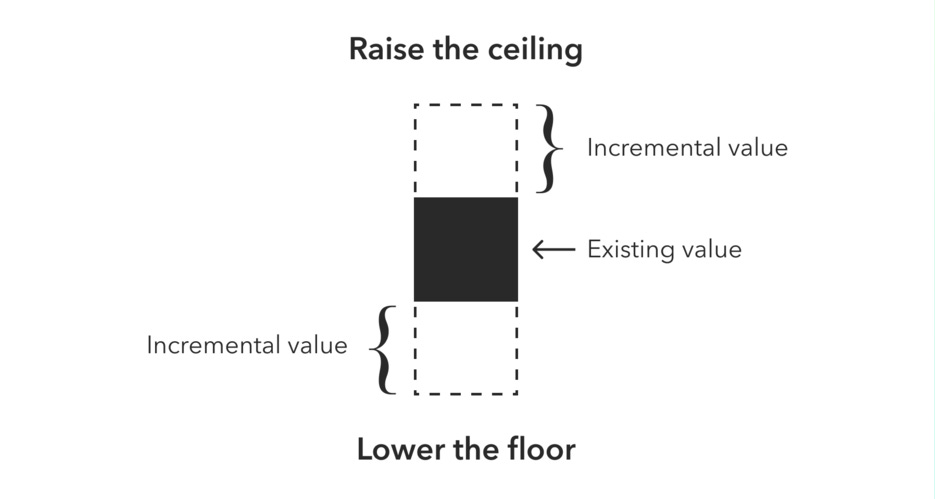

Well if you came here looking for ways to improve your performance, the answer is obvious. Putting effort to building positive, healthy lifestyle habits raises the floor of your performance metrics.

By committing to the long-game, you maximizing the opportunity to fulfill your potential! Short-term improvements are just that, short-term. And while you may get those improvements, once you’ve optimized for them you will still need to address the base layer in order to reach your full potential.

Long Term Change vs. Short-Term Improvement

Let’s look at an example:

Note: I made these numbers up. Do not use them as reference.

Background:

Johnny is a 45 year old man, sleeps ~6.5 hours/night, runs 50 miles/week, has a moderate-stress career, drinks occasionally, and struggles to get full protein recommendations. His SDNN HRV measures 75ms over a 24h period.

He wants to improve his HRV! And he read that cold showers in the morning and doing breath work drills will improve it (true, it can).

Let’s play out, from a performance perspective, Johnny’s options when it comes to training and improving his HRV:

Johnny spends the next 4-weeks taking cold showers in the morning and breathwork training daily. He sees significant improvements in his HRV, and at the end of one month his SDNN measures 125ms. Great!

Johnny commits to improving his sleep to an average of 7.5h a night, and changes his training program opting to replace 2-days of long-distance runs with shorter, higher-intensity interval runs. He does this for 6 weeks and his SDNN has improved to 110ms. Very good!

This is only a short term view. Let’s expand our timelines a little:

3 months later:

Johnny continues to take cold showers, but has lost consistency with his breathwork training. He took on a stressful business project that has challenged his training, and the invigorating feeling from the routine has lost it’s edge. His SDNN inconsistently measures between 90-100ms.

Johnny took on the stressful business project, but refused to allow it to affect his positive habit of getting at least 7.5h of sleep. By including HIIT in his running 2x/week, Johnny cut down on the time needed to train on those days, instead devoting the extra time to the project. His stress levels are lower, and he’s grown stronger from the change of training. His SDNN measures 120ms.

Sustainability matters. Viewing training as simply the result of your next performance might make you win in the short term, but you’ll be left far behind without recourse in the long term. Although this might be a rudimentary example, it illustrates the point flawlessly. How many times do we opt for the path of least resistance, the short-term improvements, in lieu of consistency over the long term?

And finally, in spirit of true performance improvement, let’s get to the best part of the sustainability approach when done right.

6 months later:

Johnny has abandoned his cold showers and breathwork training. He’s back to where he started, with an SDNN of 80ms.

Johnny is training in full stride. He feels so good that he’s signed up for a marathon. With competition 6 weeks out, Johnny began looking for ways to temporarily optimize his performance at the race. After meeting with a performance coach and seeing the strong foundational habits Johnny has established, he recommended Johnny begin a cold-exposure and breathwork program 4-weeks before the race. They follow the plan, and 1 week before race day Johnny’s HRV measures 165ms. An incredible improvement and true optimization of HRV for performance in preparation for his race day. Following the race, Johnny discontinues the breathwork/cold exposure, opting to use it sparingly before important events.

No matter how intensely or consistently Johnny practiced the breathwork/cold exposure, which is proven to have benefits to HRV, he would not be able to make as significant an improvement as he did in the second scenario where he improved his lifestyle habits to raise his HRV floor, and THEN added the optimization technique after.

One way to think about it is likened to a video game, where your short-term techniques are your power ups. They have a great effect, but require timing to be most effective. Your long-term habits are the core attributes, they determine performance over time. So while someone using a ‘power-up’ could win in competition against someone with better ‘attributes’, it’s a temporary win, and looking at their competition over time will show that those with better ‘attributes’ win a higher % of time.

Yet if you take the person with high ‘attributes’, and they learn to use the ‘power-up’ at the right time, well that person is now unstoppable.

If you can live a lifestyle that promotes a higher HRV through daily habits, and then utilize certain techniques or protocols to optimize it even further in the short-term, well then you have truly achieved performance optimization.

I hope it’s clear how important the daily habits are to raise the floor of your HRV performance. Next week I’ll show you how you can achieve short-term optimization of your HRV through breathwork. And then it will be up to you, and you alone, to take this information and apply it to your life to step further towards your goals.

Play for the game of life, not the game of tomorrow!

Have a question? Want to share your experience with us so others can learn too?

Disclaimer: This is not medical advice. The content is purely educational in nature and should be filtered through ones own lens of common sense and applicability.