Health vs. Performance

Level 1: Amateur

Welcome Players! Everyone wants to be better at something. Athletes want to perform better at their sport, businesses want to make more money, and people want to do the activities they love more often and with greater competence. Often-times the goal of improved performance can be so consuming that sight of the bigger picture is lost. Sacrifices in health become the trade-off for enhancements in performance. But what does that mean? How does one affect the other? Is that the best approach?

Contents:

The argument for Health+

Health impacts more than you think

Is it really Health vs. Performance

Busain’s Race

Performance

Veronica’s Summer

Conclusion

The argument for Health+.

What does it mean to be Healthy?

By most conventional (Western) Healthcare Models, being healthy would be a factor of reducing risk associated with chronic disease and fatality, or put otherwise, the absence of illness. These would include avoiding diagnoses of things such as cardiac/lung disease, obesity, diabetes, cancer, alzheimers, stroke (CDC stats). If you lack a diagnosable disease, congratulations! The healthcare model considers you Healthy 👍

But there is a huge problem with this approach. As stated by the World Health Organization (WHO),

Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

Most people (especially Americans) have grown up in a system where if they lack disease they believe themselves to be healthy. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

Health is the ability to fully experience the joy of living; to utilize all the amazing components we have been given; to explore our physical capabilities; to feel the depth of our spiritual and emotional connections; to experience the touch of our social relationships throughout time. It is the doing of these things that contribute to our Health, not the passive process of waiting for disease to develop.

It’s the perspective of health as a process that we have to work to adopt. You are either moving towards health or away from it, there is no middle-ground. Even when you think you are doing something to maintain the status of health you are currently at, you are not simply staying still along the line of progression. If you are in a negative-environment and actively pursue a positive-health habit, it might feel like you’ve simply stayed in the middle; a net-neutral affect on your health in the moment. But in reality you took a step forward, a step towards reinforcing the habits that will make you successful, and a buffer against the decline that could have occurred had you opted for passiveness in that moment.

Health impacts more than you think.

We’ve accepted that being Healthy is much more than avoiding disease. It’s the pursuit of wellness that contributes to our life experiences in a positive way. But can being healthy help us improve our performance?

Using one of our our 5 Pillars we’ll look at how one activity of daily life can lend it’s improvements to a potential performance-related task and see how they relate.

Physical Health → Walking → Health benefits → Improved Walking Time Performance

Physical Health.

With obesity on the forefront of chronic disease in the United States, it is well within reason to consider the ability to walk sustained periods as a measure of physical health. Even something as simple as the 6-minute walk test is used as an early-indicator for certain forms of lung-disease. The sedentary lifestyle of most people in the routine of wake up, drive to work, sit/work all day, drive home, eat/relax, sleep, repeat leads to an incredible loss of physical endurance and strength for things as simple as walking.

So how can we improve our physical health? Walk more! Start with 5 minutes a day. Then 10 minutes a day. Then 30… I’m sure you catch the drift. Soon you’ll be up to a few miles a day which is a great achievement.

Let’s look at an example of how someone looking to improve their Physical Health through walking is improving their performance as a byproduct!

Busain’s Race

We’ll call this person Busain Olt. Busain is a middle-aged, overweight male. He had a recent revelation with his neighbor Bob that if he doesn’t do something about his weight-gain now, he might never be able to get rid of it. So they made a challenge that they were going to walk/run 1-mile and see who can have the greatest improvement over the course of one month.

Busain is an avid reader of Train Like a Pro, so he thinks that his best chance at improving his performance in the 1-mile race is to slowly and steadily improve his capacity to walk the mile.

At the start of the Challenge, Busain and Bob both walked a mile in 22:30. Busain’s training plan was to walk 10-minutes a day, adding 5-minutes every other day. Bob’s training plan was to intersperse his version of running for as long as he can maintain (which is not very long) interspersed with walking intervals. He read online that High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) is the best way to get in shape faster!

Let’s fast forward to 2-weeks into the challenge, the halfway mark. Busain is up to walking 45-minutes a day, and although Bob started strong he has missed the last 4 days of his training because he was starting to get some knee pain. Busain on the other hand is starting to notice that he looks forward to his daily training walks, and that he has increased energy following. He knows that walking for 45-minutes a day is great, but he decides that for the purpose of his challenge he is going to stop adding the extra 5-minutes every other day and instead attempt to cover greater distance (walk faster) than his previous day. At this point Busain was covering 2.5 miles in 45-minutes, so he sets a goal of adding 0.1 mile distance per walk/day.

With one week left until the final challenge, Bob is back to training but has lost a portion of the progress he made due to the time off he had to take from his pains. He’s unmotivated and pessimistic that this challenge is going to help him at all. He would have given up by now had it not been for the sight of Busain leaving his house at the same time every morning to embrace his walk.

Busain is a full-fledged walker now. He’s covering 3+ miles in 45-minutes, bought himself a proper pair of walking shoes, and makes sure he’s hydrated every morning before he goes out. He can’t wait until the time for his walk, and is moving at a pace he’s never done before. T-minus one week until the final challenge, and Busain is excited to see how his time has improved!

Race day!

Bob takes off from the start-line with a heavily compensated run, he makes it about 100 yards before he pulls up into a labored walk. It’s going to be a long mile for him.

Busain on the other hand leaves the start line with a brisk pace that he’s more than accustomed to by now. He thinks he can go even faster, but wants to stick to the plan and stay consistent throughout the final walk to see his true progress.

Busain finishes the 1-mile walk with a finishing time of 16:30! He finishes exuberantly, full of energy, and is craving for more!

Bob finishes with a final time of 20:10, no contest to Busain’s improvement but certainly improved against his 1-month prior starting point. Bob finishes with labored breathing, some minor pain in his left knee, and is glad this stupid challenge is over.

Who’s healthier?

This may have been a rather rudimentary example for many of you, but it highlights how simple the concept is yet how many people choose to ignore it.

Busain and Bob both improved their 1-mile time throughout the challenge. Without question their performance both increased, but whose was more effective?

Bob opted to attempt to improve performance without first establishing a foundation of health. He skipped a proper progression of walking to running, and did not account for how far behind his cardio-vascular system was in conditioning. While he may have improved performance in relation to the time at which he completed the mile, his heart health, measures of blood-pressure, cholesterol, capacity to fend off cardiac/lung disease, and beneficial effects of exercise are all no better off with Bob’s approach. His performance was also temporary, for after 5-days of inactivity his conditioning will return to it’s former levels, holding no long-term effects from his month of effort. He also has developed a compensation pattern for his knee pain, which although the pain has subsided, the compensation has not and he walks with a minor, yet noticeable, hitch.

Busain on the other hand focused solely on improvements to his Physical Health and had hoped that they translated into performance improvements as well. His assumption was correct. He improved his mile time by almost 27% through the implementation of progressive increases to walking time and speed. He built capacity slowly, starting at a low level that matched his current abilities. He suffered no injuries or set-backs, and experienced incredible benefits in the other pillars of his health that he did not expect. His mood improved, his energy levels throughout the day improved, and he was looking forward to his daily exercise instead of dreading it. Busain’s wife noticed the change too, as he had shrunk 2 entire waist sizes throughout the process. Busain has no plans to stop his newfound enthusiasm for walking. He is debating what to challenge himself with next, but knows that it will build upon the progress he’s made in the 1-mile. Maybe 2-miles is next?

Its not Health vs. Performance

You see, attempting to improve your performance at something that you have not yet reached adequate foundational levels of health in will not bring you the benefit you thought it would. Health IS the foundation to performance.

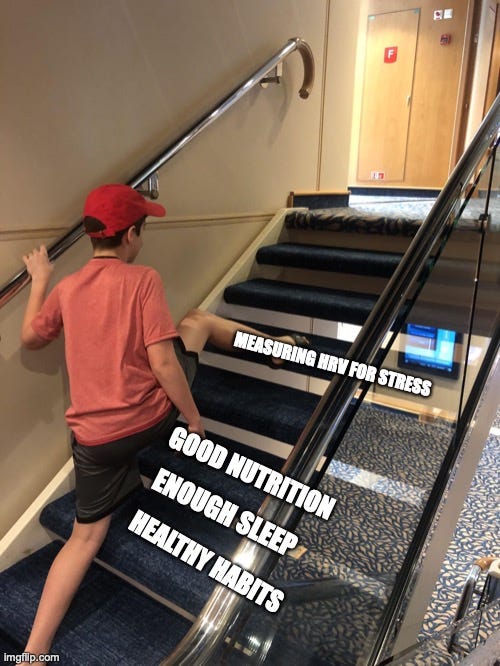

The most efficient and sustainable way to improve your performance is to first establish a baseline of positive Health habits, and then you can train improvements to specific attributes. Even then, oftentimes the highest expected value of improvement can be found in optimizing the habits. Once you’ve set yourself up for success, training specific attributes becomes a highly intelligent way to achieve the goal you want.

Performance

What is the best way to improve performance?

I hope by now you anticipate that is a loaded question. It depends on what it is you’re doing, how you gauge improvement, what you define ‘best’ as. One reason it is so difficult to clarify the best way to do anything in the Health, Wellness, and Fitness fields is because of the vast amount of independent variables. Each unique individual is an independent variable, along with their life experiences, habits, and decisions. Any respectable cohort study on chronic disease needs tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of data points to even be taken with a shred of credibility.

Yet when we see the “Best Way to Lose Weight” or “Best Way to Gain Muscle”, our consumption society thinks whole-heartedly that they are about to find out the magic recipe to a timeless question, in less than 15 minutes!

In order to have the conversation of what is the best way to improve performance, we have to define exactly what we mean with every one of those words.

The best way (pun intended) I’ve found to be able to do this is to use a very specific example, and then unwind it from the end to explore the prevailing concept. You may have noticed by now that my writing is very example-heavy, and hopefully my pseudo-naming creativity improves (no promises).

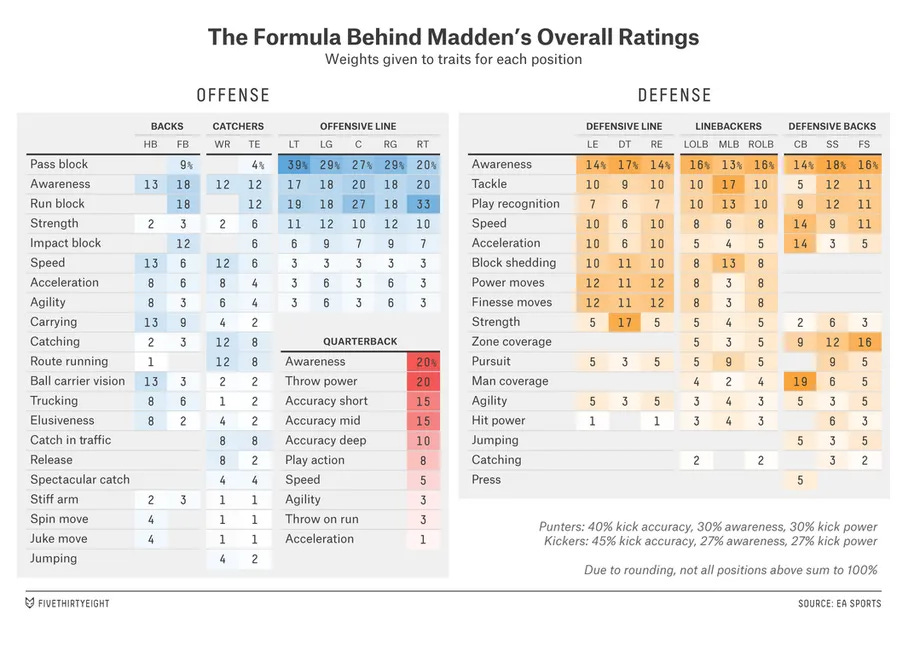

In this example, we’re going to look at it as if we were creating our own player in a video game. This was always my favorite gameplay-mode as I loved the strategic creativity aspect (you get X points to spend on Y attribute improvements). The goal in my mind was to find the most efficient way to spend the improvement points to translate to improving my characters ability to play. There was no one right way to do this, as you would always be balancing trade-offs for improvements in one skill vs. deficiencies in another. But this is very much like real life. Except our ‘improvement points’ are our time, and the ‘attributes’ are our competency at a skill.

Want to (insert goal here)? Spend (amount of time) on (attribute required).

Want to be stronger? Spend at least 3 days/week resistance training.

Want to learn to cook? Dedicate one meal a day to making a new recipe.

Want to reach enlightenment? Spend the rest of your life searching for balance.

Some attributes cost more than others, but in the end there is always a direct payoff between how much time and energy you dedicate towards improvement and the resulting improvement sought. With that in mind, let’s explore an example of how one young athlete can change their mindset from improving performance to improving health, and do both.

Veronica’s Summer

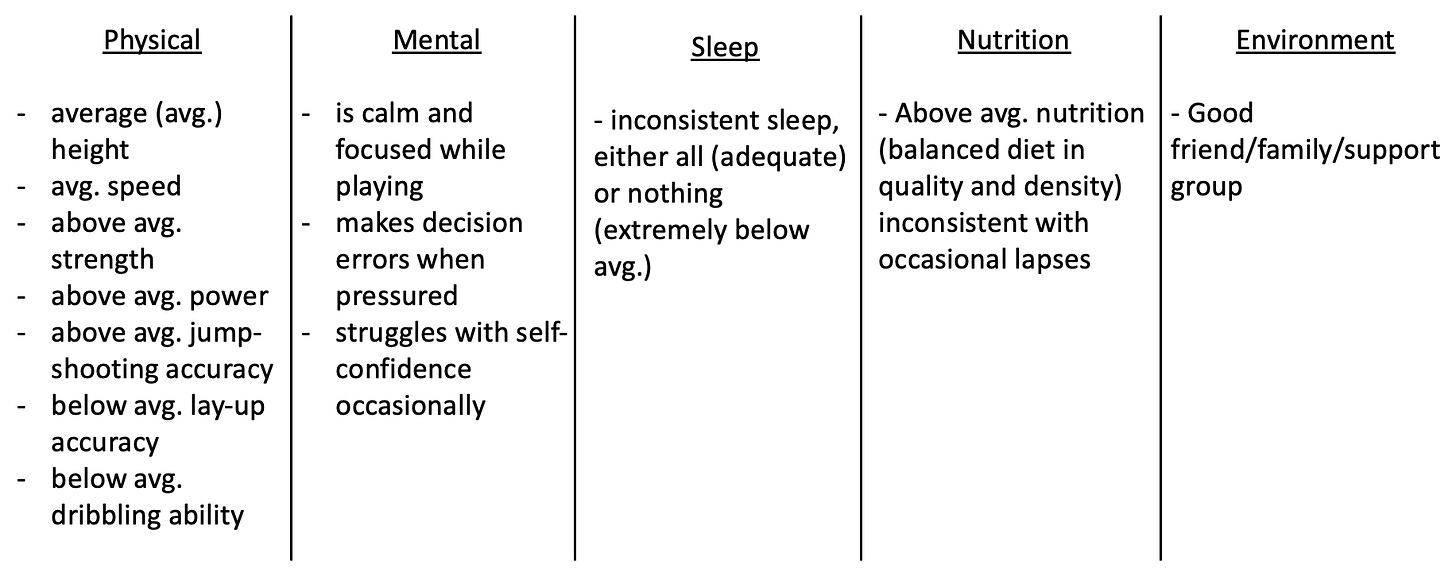

Let’s take Veronica James, an up and coming high-school basketball player. She just finished her freshman year, and has 3-months of summer to improve her playing ability before Varsity try-outs. Some background on Veronica’s 5 Pillars:

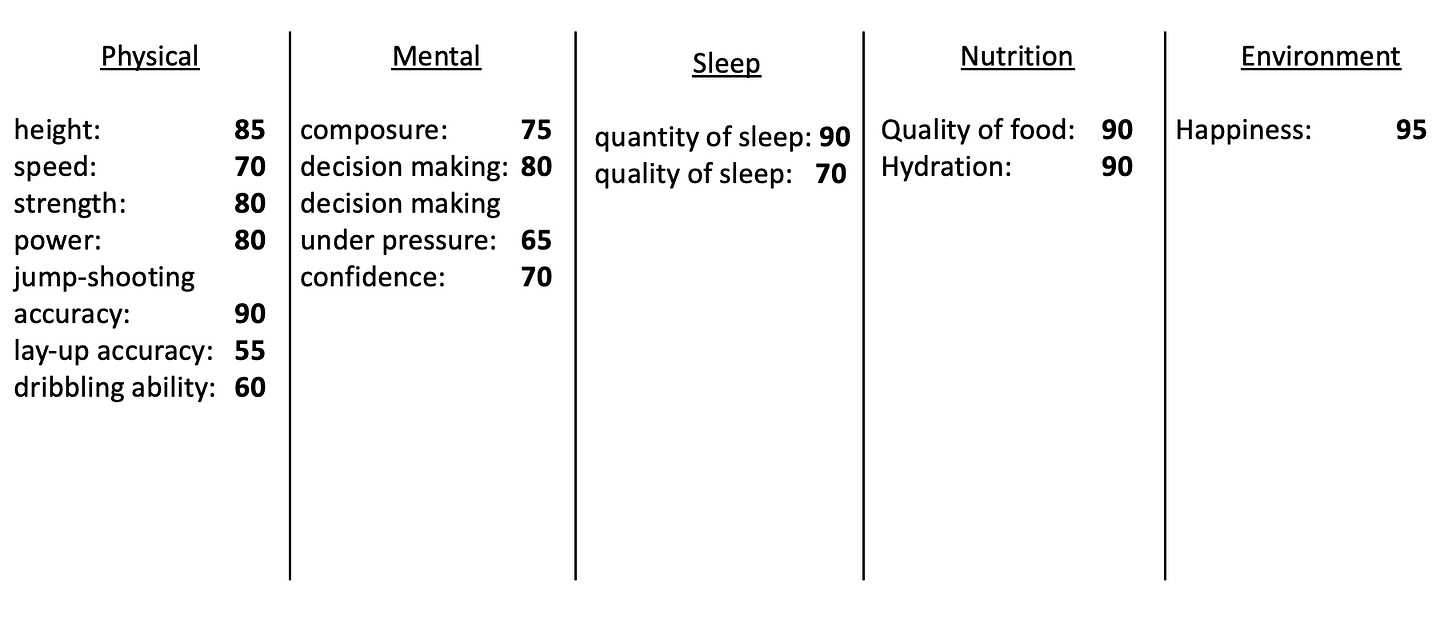

Now let’s gamify it. I’m going to re-write Veronica’s background/current ability as scores on a scale of 0-100, where 0 = worst and 100 = best as it relates to the maximum unit of that ability. Of course these are subjective for now, but let’s pretend there’s an extremely intricate and systematic formula that dynamically adjusts one attribute score with another. For example, the scoring ability score is a dynamic combination of both jump-shooting accuracy + lay-up accuracy. The % change in improvement in scoring ability will not be the same from improvements of jump-shooting accuracy 75→80 as it would improving lay-up accuracy 60→65. Video games have to fully complete the formula in order for the game to work, but we have no such luxury in the real world.

Veronica’s summer is 12 weeks long, with each week she earns +1.25 improvement points from time spent practicing. Let’s assume Veronica is in love with the game of basketball, and spends an excess of her time points (of which she is given 24 every day) on practicing. At the end of the summer, Veronica will have made 15 points of improvement in any combination of the attributes listed, in any of the 5 Pillars.

Take a second now, and think if this were you, how would you be improving your character?

A performance-first approach would look at at her physical attributes and spend the entire summer on trying to improve them. Most common answers would probably say you go +5/10 on lay-ups because that is the lowest hanging fruit and will have the most carry-over to her in game ability by not being an exposed weakness. The other +5/10 you probably want to address dribbling, but arguments could certainly be made for maxing out her jump-shooting accuracy and being elite there. Any leftover points you throw at speed/strength/power and hope they hold a good weighting against some of the other basketball-specific attributes. This is an approach many have tried, and certainly when fall try-outs come around there’s a decent chance at making varsity if you’ve done everything right.

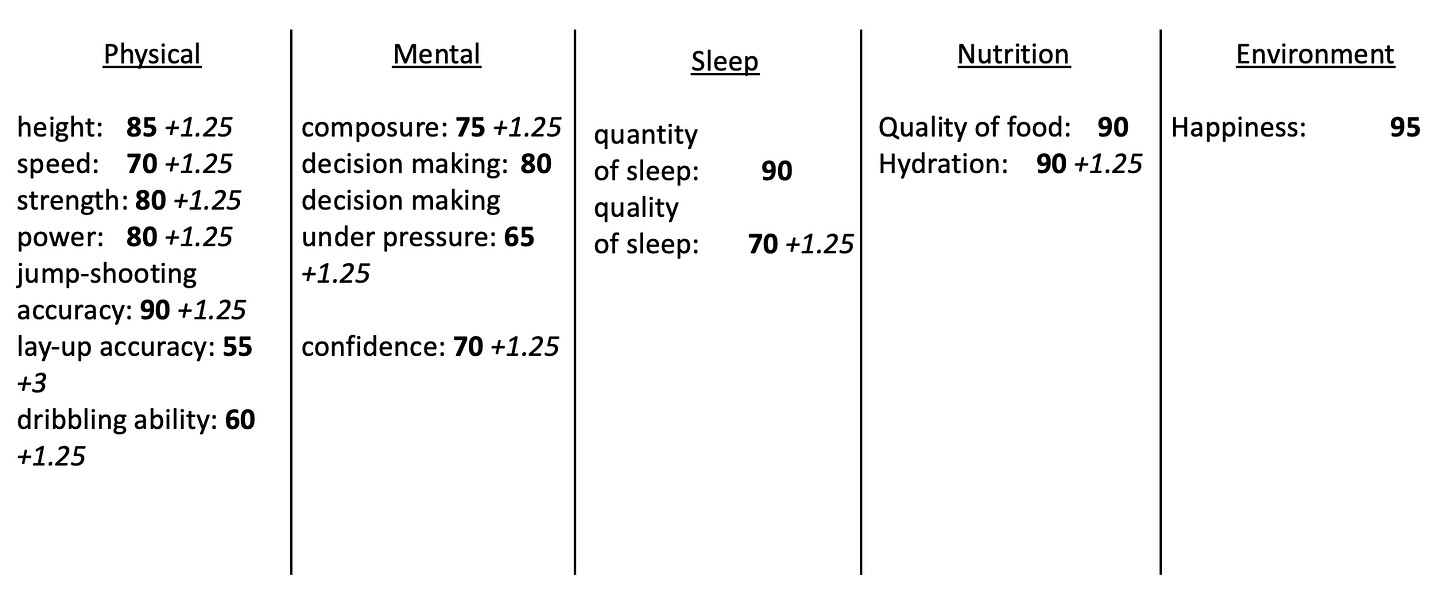

But what about the sustainable approach? The not-so-sexy approach. The slow-and-steady wins the race approach. The one where you split up all your improvement points appropriately after a carefully and thoughtfully laid out analysis of what you think will improve your overall game the most, or at least make the improvements necessary for the goal you set? This approach does not see Veronica become the best player on the team her sophomore year, and maybe she doesn’t even make varsity that year. But come the year after, and the year after, when this approach begins to compound because of the consistency, where her performance both on the court and in the attribute tree has risen to a level that has no weaknesses, is well-rounded, and emphasizes parts of her skill that give her a performance edge against her competition Veronica will quickly be identified amongst the best basketball players in comparison.

That might look like:

Now this looks like Veronica did some serious training. But there are the same amount of points (15) we used before, except this time split them up in much smaller increments. The magic is not in the improvements to the attributes themselves, but knowing where to spend the time and energy on to where it will have the greatest effect on playing ability, or performance. In Veronica’s example, small improvements in confidence, decision making under pressure, and calmness will all have a positive effect on dribbling ability and jump-shooting accuracy. Her lifestyle improvements of quality of sleep and food enhance almost every other attribute, as well as amplifying the physical improvements she did make.

It’s nearly impossible to come up with a sequencing that could account for the interactions between all of our bodies systems and the time spent on improving certain aspects of them. Video game rating systems don’t get the credit they deserve for being as complex as they are, and yet they pale in comparison to the interactions of reality.

Nevertheless, the answers are still there. We must use scientific knowledge to provide the basis of support on theories of improvement and test them against time and experience. It is the only way! If we take Veronica out of our video game example and put her in front of us, we can say that by her spending the summer on building positive sleep habits, continuing to enforce a quality diet, and spending reasonably amount of time practicing a range of skills she will be well prepared for competition and more likely to sustain these improvements over the course of her career.

Health → Performance

So how does this relate to you?

The purpose of these examples was to hopefully make it simple to understand that before you attempt to intervene in improving your performance at something, you should first look at what foundational components of health are necessary to support advances in performance.

In Busain’s Race, we saw that simple progressive activity provided a foundation for living an active life and combatting chronic disease, providing a launchpad for consistent exercise.

In Veronica’s summer training, we saw the positive effect that chasing improvement over competency can have on a growing high-school basketball player.

What are you currently trying to improve? Have you thought about how maybe the best way to improve it is to actually develop improvements in something else first?

I take nootropics to enhance my cognitive abilities and improve my work efficiency.

Do you eat a balanced nutritious diet and receive adequate hours of consistent sleep?

I work out twice a day (1hr cardio / 1hr resistance training ) to maintain muscle mass & stay in shape.

Have you optimized your workout routine or considered utilizing a more efficient training modality to achieve the same goal? Does your nutrient profile match your training goals?

I have to drink 3-cups of coffee a day to wake up in the morning. But I’ve always been like that!

Are you cognizant of the factors that influence your circadian rhythm and sleep? Do you view sunlight at optimal times? Do you restrict artificial light before bed? Do you prioritize sleep habits? Do you eat a well-balanced diet conducive to energy levels?

More often than not, there is a more efficient way you could be improving your performance for a goal, and it has nothing to do with performance at all. Focus on factors of your health and think about how they could be contributing, or inhibiting, to how you perform. Only when you have built a strong and deep foundation can you construct a house capable of weathering the largest storms.

Health & Performance are on the same continuum of progress. Build your health as the foundation of your performance, and you will reap improvements more significant and for far longer than you would otherwise.

Has this changed your perspective on any approach to training or improvement you’ve been trying to make recently? Let me know in the comments!